A Gathering of the Klan

From The Gator Growl Number 87 for March 1983; winner of Prose Non-Fiction laureate award.

It was a muggy Sunday morning in August 1956. I can't say I felt overwhelmed with bravery as I bounced off the blacktop road into the backwoods of Northeast Florida. I was following directions given me to a meeting of the Ku Klux Klan, and I knew I would not be welcomed.

The managing editor of The Tampa Tribune, V. M. (Red) Newton, sensed a story no matter what happened. Race relations were simmering in Florida that year, as diehard segregationists sought to stave off the inevitable-integration of public schools.

I had spent the night in a motel in Starke, some 25 or 30 miles from the eventual destination near the town of Macclenny. Somehow I had no trouble awakening early, gulping down a quick breakfast and zooming my Plymouth toward the rendezvous in the woods.

As I bumped over an unpaved trail through dense pines, I wondered why no other cars were headed in the same direction (I later learned that the route given me differed from the rest). Eventually in a clearing I spotted a fenced area filled with automobile and unmasked men milling around a tin-roofed building. As I approached the parking area, and sought to turn into the field, one of my rear wheels lurched into a ditch. Several bystanders helped give me a push, and I went ahead and parked inside.

No sooner had I turned off the ignition and opened the car-door than I was confronted by a young man asking almost cordially for a wallet card of some sort -- confirmation of membership in that particular branch of the KKK. Of course, I had nothing but a driver's license identifying me as a newspaper reporter (at that time The Tribunedidn't even issue press cards). I knew it was futile to try to bluff my way any further.

"I guess this is a good a time as any to tell you that I'm a reporter from The Tampa Tribune, and I was sent here to write about your meeting today," I said.

The smile of cordiality quickly froze into a scowl, and my greeter said, "Better get back in your car. There'll be somebody out in a minute."

I could hear the hymn "The Old Rugged Cross" being sung inside the nearby building. The singing stopped abruptly, and suddenly about 100 people streamed out into the parking area and surrounded my car.

There were loud shouts and questions, "Who sent you?" and one beefy, redfaced oldtimer in particular started cursing me and The Tribune. There were angry inquiries why I was meddling in their business. I simply told them I had been sent to write about their meeting and whatever they had to say. The beefy oldster snorted threats and revenge for invading private property. But at this point another man, apparently an officer, said politely, "The klavern wishes you to leave."

I didn't dilly-dally. I said I'd leave -- and I managed to get the car started and out of the parking area without any further problems with that ditch. I emerged from the woods a short distance later headed eastward on the main highway to Jacksonville, where I had to write the story and prepare for another North Florida assignment. As I was driving at a good rate of speed, though, I noticed two cars following closely. Within a few seconds they had forced me to the side of the road.

As I sat and waited behind the wheel, I thought my days as a non-violent reporter were probably ended. That interval as about eight men approached was one of the longest "waits" of my life.

A burly hand reached through the open right window and opened the car-door. I thought, "This is it."

To my amazement, the first words I heard were: "We just wanted to apologize for the rough language back at the other place."

Well, I got out of my car and stood on a lonely roadside for about 45 minutes talking to those Klansmen. It was obvious they felt they didn't need a "bad press" at that point, but it was also obvious they wanted to know how their secrecy had been breached by a reporter from a downstate newspaper.

They kept asking my motive in coming and how I had known the location of the meeting. I could truthfully answer that the directions had been given to me by my editor and I didn't have any idea how he'd gotten them.

I told them I was there to report what happened, including their views if they wanted to express them. This resulted in quite a denunciation of race-mixing in the schools. One man pointed to a service emblem tattooed on his arm and said, "I was ready to lay down my life if necessary once before, and I'm ready to do it again."

Several of the Klansmen said they were sworn to uphold the state laws then still in effect on segregation.

Periodically, as the conversation continued, there were hostile questions pointed at me and I wondered whether this followup get-together was going to be peaceful after all. They kept asking my name, and I had no hesitancy in telling it.

Finally, one grisled oldtimer asked if I was related to "ole Cap'n Hawes in Elberton, Georgia." I told him that was my great-uncle who had reared my father after his parents died.

Apparently the recognized name of a relative who was prominent in his hometown broke the ice. From then on, the interview wound down calmly. In fact, the Klan members expressed such interest in what I planned to write that several asked me to send copies of the article once it was published.

The article appeared the next day, Aug. 15, 1956, with a staid one-column headline and a "straight news" narrative of the interrupted Klan meeting and its aftermath.

The account concluded with this paragraph:

"After Klansmen discussed their intentions to oppose integration in the schools, the conversation was ended and the men returned to their cars. The reporter continued on his way."

The only thing missing was a final personal comment from the reporter: "Whew!"

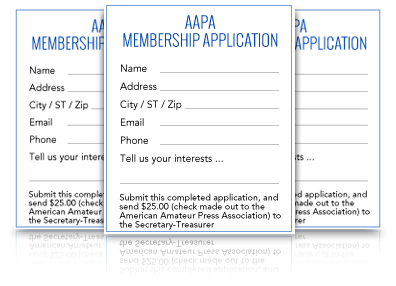

JOIN AAPA!

Become A Member!

Amateur journalism is a unique activity. Amateur journalists publish journals on paper & online & come from many perspectives: from deluxe letterpress printed journals, to Xeroxed newsletters, to artistically designed cards and ephemera. We embrace the spirit of being amateurs – loving what we do for pure joy and not financial gain – while creating top quality journals, zines, and homemade publications.

Amateur journalism is a unique activity. Amateur journalists publish journals on paper & online & come from many perspectives: from deluxe letterpress printed journals, to Xeroxed newsletters, to artistically designed cards and ephemera. We embrace the spirit of being amateurs – loving what we do for pure joy and not financial gain – while creating top quality journals, zines, and homemade publications.

Members receive ...

- The monthly bundle mailed via the postal service

- Access to the website and e-journals

- e-mailed updates

- Ability to publish your stories on AAPA

|

|