From Thonotosassa to Tampa

Originally published by Leslie W. Boyer in The Echo Number 71 for May 1965.

The boy becomes the man and the amateur journalist becomes the professional journalist -- sometimes. When this happens the amateur interests are often submerged. A notable exception is the dual career of Leland M. Hawes, Jr. His is a skillful blending of professional and amateur achievements.

Hawes entered amateur journalism formally when he joined the American in 1942, age 13. His address then was Thonotosassa, Florida. Actually, he was an amateur journalist two years before that when he published the Flint Lake Diver, a neighborhood weekly.

He has been President of the American twice, Official Editor three times, and has held various other offices. He received a B.S.in journalism from the University of Florida in 1950. His professional career is with The Tampa Tribune. There he has gone from cub reporter, through special assignments and the editorship of the Sunday feature section, to his present post in the editorial department.

These are the statistical bones of his two careers. They need the clothing of characteristics to depict a very remarkable individual.

A word that first comes to mind in knowing, thinking, and writing about Hawes is quality. It is apparent in every, thing he does, everything he is. It is in his development as a career newspaperman. In his career as an amateur journalist and in his permanent stewardship of the AAPA. In his personal journal, Gator Growl. In his personal appearance and apparel, the appointments of his home, his individual tastes and pursuits.

One day at a Washington, D.C. convention of the American, Marge Adams dubbed Lee Hawes and Vernon Forney "all-American boys." She spoke in the broad, physical sense. In a more specific, associational sense, Lee Hawes is American, all-American, all the way. His loyalty to it is solid, unswerving, unselfish. His constant vigilance in expanding its membership, raising its standards, improving its morals, is unparalleled. He has spent uncounted hours of time and dollars of personal money in advertising in magazines for new members. In writing letters to re-establish contact with former members. In publishing -- in 1962-64 -- a modernized, enlarged American Amateur Journalist.

With the cooperation of others he spearheaded the Silver Spur program of the American in its anniversary year. This campaign reactivated former members and found some new ones. It revived and rejuvenated an organization on the way to atrophy. He has already had all of the honors as well as the onerous duties that officeholding in the American can give him. Yet his interest in the American is so deep, his attachment to it so practically sentimental, that one sees him guarding it forever, like a stone eagle perched agelessly on a balustrade.

In Growl No. 67, Hawes writes of an incident at a "big banquet" at the Hotel Statler (Washington) but neglects to mention that he was attending the annual convention of the NAPA. Although he belonged to the National for some years, and occasionally attends its conventions as a quiet observer, he consistently avoids involvement in its official affairs. Except for Laureate Judge for editing in 1954, he has never held an appointive or elective office in the National. To expect him to take a National office is like asking DeGaulle to succeed Dean Rusk.

The corporate precincts of The Fossils seem more neutral, however. He joined in 1957 and has been Secretary-Treasurer, and a Vice-President twice. In January 1964, as First Vice President, he succeeded to the Presidency when Helm Spink resigned. He was elected to the same office in April 1964.

Lee's mother is from South Carolina, his father, from Georgia. The family revenues stem from citrus groves. The family residence is a large, dignified house in a tree-shaded yard, at 822 South Orleans, Tampa. It has deep, cool porches, high-ceilinged rooms, and its furnishings -- including large four-poster beds, some of them canopied -- display the senior Mrs. Hawes' liking for antiques. His father's special interest is the history of the War Between the States, and one of Lee's pleasant annual chores is to find a new book on this subject for his father's Christmas gift.

This atmosphere, plus the characteristics which are inherently Lee's own, make him a Southern gentleman with the good manners, the diplomacy, the friendliness, the hospitality that this implies.

Lee is of medium height, fine-boned, subtly sharp-featured. His thick dark hair is always well-oiled, well-brushed. His eyes are inscrutable, possibly a composite of grey/blue/hazel. His smile is ready and wide. He dresses well but unobtrusively: dark suits, ties with subdued stripes. As befits a Gulf Coast Floridian, he wears shorts on informal occasions and sometimes permits himself the flamboyance of a patterned sportshirt.

He likes the theatre and annually wangles one or two trips to New York for a circuit of Broadway plays. He likes music and he likes books. The shelves in the livingroom of his house are filled with books, many of them bright-jacketed, others in the somber tones of "volumes." More books overflow onto shelves at one side of the breezeway off the diningroom. They range from "The Works of Geoffrey Chaucer" to "A Treasury of Modern Reporting." They include liberal samplings of Thomas Wolfe, Scott Fitzgerald, Hemingway.

Hawes' chief personal journal is Gator Growl. Occasionally he mimeographs an Amateur Parade. Growl began as a mimeographed journal, but in recent years it has been printed by Russ Paxton, to Lee's exacting specifications.

Growl features clear colors -- green, scarlet -- on its covers. Some covers simply show the title, in big type. On others, an angry alligator in color, the original drawing by someone named Murphy, is rampant. Inside there is effective use of bold heads, large type, much white space. Photographs are used occasionally; the ornaments beloved of many publishers, never. Sometimes there are vagaries of makeup, as in No. 73 in which the heads, in bold thick black type, span two pages.

Hawes was editor of Panther, his high school yearbook. This was the beginning of an incisive editorial ability which diversifies the Growl ideologically and in narrative style. He solicits -- and gets -- articles and some fiction from amateur journalists of all kinds. He uses poetry sparingly.

He achieves in the Growl, both in format and content, the certain, clean, singing line of a Toscanini. This extends to his own writing in his journal, which is conversational in tone, lean in execution. There is occasional effective use of literary phrases such as "the relaxed sprawl of sleep" in "Havana, 1959" (Growl No. 69). He credits early exposure to the late Burton Crane's "meat axe" school of writing for his own staccato sentences.

This, plus his reportorial training, makes many of his articles a series of one-sentence paragraphs. In contrast, his personal letters are chatty, informal, often long-sentenced, long-paragraphed. They are black-ribboned and pica-typed on a Royal standard office machine in his second floor study. The letterhead is excellent white bond (currently Strathmore), 8-1/2 x 11 standard business size. His name and address are printed in bold black letters at the top center. His signature is in blue ink, with a broad, pointed pen, and the two e's of "Lee" are in only slightly smaller caps than the L.

Hawes' current home is at 5009 Dickens Avenue, Tampa, chosen for the special qualities of the house and not for the literary connotation of the address. He deliberately sought and waited for a house of distinction and comfort. What he found is not the usual ticky tacky ranch-style or split level box. Instead, it is a graceful two-story house set in the sub-tropical green of a large yard, with tall palms in front, and a grapefruit tree in a sideyard.

The livingroom has a fireplace at one end and a staircase at the other, which leads to a narrow balcony across the front of the high-ceilinged room. This balcony needs only fat musicians tootling on archaic instruments to suggest medieval days. The walls are textured white. The rug is dull gold, the divan turquoise, two occasional chairs are green, two others a mingling of greens and blues. These colors are repeated in the candles on the mantel. Among the pictures on the wall is a watercolor signed by Jack Coolidge, and given to Lee on his European journey when he visited Jack in Florence.

The basic furniture in both the livingroom and dining, room is Italian provincial, and the diningroom rug is a dull gold companion to the one in the livingroom. The hi-fi is in the archway between the two rooms. On one wall of the diningroom is a Grecian head, purchased on the European trip, and mounted on black velvet. On another wall are two unusual fabric hangings which have abstract designs in clear orange/red and turquoise colors reminiscent of the colors of a Growl cover.

If all this is a picture of a man of competence, wide interests, and flawless taste, it is accurate. If it is also a picture of one who is too selfless, too diplomatic, too dedicated, it is inaccurate.

In his professional career Hawes has been exposed to all of the mental demands and some of the physical hazards of the modern newspaper world. He has covered spirited political campaigns. He has had special assignments from his newspaper involving underworlds in which one would not expect to find one of his demeanor and refinement. He was dispatched to Havana in the very first days of Castro's Cuba and later wrote about it in a Growl.

In the area of amateur journalism's politics and administration he is a man of firm conviction, shrewd perception, quiet but determined action -- and benevolent ruthlessness. He assesses the performance of amateur journalists currently, and mentally indexes those who are undependable or non-productive. These individuals are not invited to hold American office.

When, a few years ago, some aspects of American conventions became too liquid, Hawes gave no outward and visible sign of disapproval or distress. However, at the next convention, a local chairman was firmly in charge of an agenda tight with forums and other time-occupying events, and the atmosphere was suitable for teenagers as well as other members.

Later, Hawes was in control of the evening program of another organization, an annual event noted for long-winded speakers. Again, with no advance warning of change, the speakers were handed their assignments on slips of paper shortly before the program began, and a standard minute limit set for each one. It was observed.

Lee has met many amateur journalists and his private assessments of them usually are objective and devoid of gush or gossip. Now and then, however, they are adverse.

At a first meeting with a prominent amateur journalist -- in a group -- Lee found the verbal antics of this character so monopolistic and boring that he has never forgotten it. On another occasion he had a luncheon appointment with an amateur journalist who was his literary hero and amateur journalistic mentor. Since the proper subject of amateur journalists is amateur journalism, probably Lee looked forward to an hour of good shop talk. Instead, the amateur journalist saw friends from another area of the arts in which he was then interested, and the luncheon period disappeared in conversation with them. Again, there was no outward sign of disapproval but one senses, in his telling, Lee's disappointment and some disillusion.

The distance from Thonotosassa to Tampa is only a few miles, but in the years since he made the journey Hawes has developed remarkably, both as a professional and as an amateur. Now he is starting another aspect of his amateur career. He acquired a Sigwalt hand press a few months ago, through the American plan, and press and typecases now dominate his kitchen. Since he is a scion of citrus groves, his press appropriately is called the Citrus Press.

In a 1963 issue of the American Amateur Journalist, Lee said that the American had, among other things, enabled him "to sense the esthetic strengths of simplified typography." Now that a new journal, June Bloom, is in preparation at the Citrus Press, the American eagerly awaits a first look at its esthetic strengths, its staccato sentences.

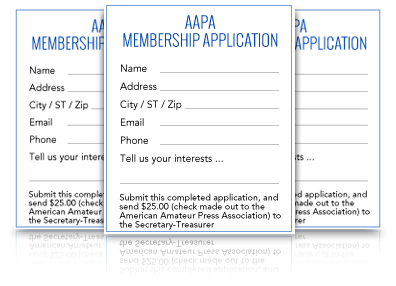

JOIN AAPA!

Become A Member!

Amateur journalism is a unique activity. Amateur journalists publish journals on paper & online & come from many perspectives: from deluxe letterpress printed journals, to Xeroxed newsletters, to artistically designed cards and ephemera. We embrace the spirit of being amateurs – loving what we do for pure joy and not financial gain – while creating top quality journals, zines, and homemade publications.

Amateur journalism is a unique activity. Amateur journalists publish journals on paper & online & come from many perspectives: from deluxe letterpress printed journals, to Xeroxed newsletters, to artistically designed cards and ephemera. We embrace the spirit of being amateurs – loving what we do for pure joy and not financial gain – while creating top quality journals, zines, and homemade publications.

Members receive ...

- The monthly bundle mailed via the postal service

- Access to the website and e-journals

- e-mailed updates

- Ability to publish your stories on AAPA

|

|