That Operation

From June Bloom Number 4 for August 1970; winner of Prose Non-Fiction laureate award.

Every now and then, someone besides an insurance man or a minister reminds us that we don't hold any permanent claim on Our Little Corner of the World. When it's a doctor who says there's an unexplained spot on that X-ray film of your chest, you listen very carefully indeed.

It was pure happenstance that I even bothered to venture a visit for a physical checkup last March. The internist, a friend from high school days, had telephoned to ask for some background on a recent Tribunearticle. When I called back with the information, I told him, "Every time I see you, I say I'm going to come by for a physical, but I haven't. Today, I think I'll go ahead and make an appointment."

I did, and I thought rather smugly that it should be a breeze since there wasn't an ache in my body. The last time I had been examined thoroughly was in 1963, when I thought I was getting the chronic newsman's ailment -- an ulcer. But that had cleared up long ago.

That Monday in the doctor's office, the tests seemed to go routinely enough. But when the wet X-ray print came back for scrutiny, there was an unidentifiable object in the right lung. Further X-rays were arranged for that afternoon, to determine whether this might be the shadow of a calcified scar from an old, undetected case of tuberculosis. But the X-rays ruled out calcium.

My doctor friend said this left three possibilities: a lung tumor, a hystoplasmic fungus or a current case of tuberculosis. Skin-punch tests in the arms showed negative results for the fungus and the TB. So this indicated the rather strong probability of a tumor -- with the nagging possibility of lung cancer.

The diagnostic physician then referred me to a surgeon, another friend from school days. After scanning the X-rays, the surgeon advised an operation. He was reassuring, though, taking note or the fact I'm a non-smoker. "If you were a heavy smoker, there would have been little doubt what that spot on your lung would be," he said. Even if it proved to be a malignancy, he went on, it seemed to be small and localized and at an early stage.

I was already prepared in my own mind for the likelihood of surgery, and I wasn't eager to prolong the suspense. The operation was scheduled for a week from that day at Tampa General, the hospital where I was born.

That week of waiting was not the most placid I've ever spent. Yes, I was confident of the outcome, primarily because of the early discovery. Still, any surgery is awesome, and no matter how optimistic one might be, there are those moments in the middle of the night when bravado dissolves and fear of the unknown takes hold.

By the weekend, I had taken care of another long-neglected chore: the making of a will. Another classmate, who specializes in admiralty law, very kindly worked me into his busy schedule to prepare the document. He mentioned in passing that his only casualty in the years he had handled wills was a 95-year-old man who had simply succumbed to the years. He said he didn't expect me to spoil his record.

Although I didn't exactly blab it around, I made no secret of my impending hospitalization. And I was grateful for the comforting words of friends. Until then, I hadn't realized just how bolstering they can be in a time of worry.

That Saturday night, as we were putting the finishing touches on the Sunday paper, I wondered how long it would be before I'd be back at these familiar tasks. And Sunday's church service seemed more meaningful than most.

Monday afternoon I was in the hospital, getting set for Tuesday morning's surgery. Somehow all the tension was gone, and I was eager to proceed and do what had to be done. When the appointed hour arrived, the euphoria of sedatives had me scarcely aware when the injection of sodium pentothal occurred.

And of course, I didn't regain any degree of consciousness until hours later, when I became fuzzily aware of nursing instructions in the intensive care unit. There was a motor humming nearby, tapping any residue fluid from my lung, and there were the usual tubes depositing glucose and other vital juices.

Strangely enough, after that week of suspense, it didn't cross my mind to ask anybody what had been chopped from my chest. When the surgeon came through the following morning, he did intrude upon my dopiness with the happy word that the operation had been a success. He said he had found a small capsule called a "granuloma." It was out and being examined in the lab, and I'd be okay.

Amid the shared miseries of an intensive care area, where about 12 people were feeling varying degrees of pain, it wasn't easy to ask questions. Nurses were demanding periodic coughs from me -- no easy order after chest surgery -- to loosen mucus and to ward off the potential of pneumonia. They were also firm in following doctors' orders about frequent turns in bed, even onto the side with the stitches.

But into a regular hospital room with a couple of special nurses, the recovery period eased off into a strength-regaining endeavor th at progressed well. Visitors and flowers filled my room, and I was glad to see them. Comparing my experience with an earlier bout with a knife 20 years ago -- an appendectomy -- I had to conclude that I felt better sooner after this one.

The laboratory results brought word from the doctor that the capsule removed had been tubercular. Eventually, it probably would have developed into a lesion. Gone, it was no longer a problem, I was assured. A few pills daily were prescribed to rid me of any remaining TB tendencies.

I was out of the hospital and recuperating at my parents' home within a week of the surgery. Each day, I walked a few more steps, petted Herbert the cat and ate heartily. My folks live in a relatively old residential area of Tampa that still has its charm, with numerous trees lining every street. I was convinced this was the greenest spring ever.

Several weeks after leaving the hospital, I decided to remove the last remaining bandage -- and I almost passed out in front of a bathroom mirror. Not that the scar was all that gruesome. But the incision had left a fullness of tissue in an unexpected spot! Here I was, with a slightly bulging right breast.

When I returned for the weekly checkup with the surgeon, I asked him if he realized what he had done to me. He took a long, side squint, couldn't resist a grin, and said, "If you were a woman, you'd be glad!" And I couldn't resist replying in mock anger, "Well, I'm not -- and I'm not!"

This quasi-comical aftermath had me wondering whether another operation might be necessary to enable me to swim on a beach without feeling like a self-conscious freak!

But the doc was insistent that "It'll go down, just give it time," and it is going down -- slowly.

As part of the back-to-normal routine he urged daily exercise, something I've seldom managed in my rather sedentary routine at the newspaper. And since I'm one of those characters who's so inept at athletics that I flunked tennis in college, I'm not exactly eager to show off my fumbling ways.

Ironically, this has been the summer of the swim. The first day I alighted from my car at Tampa's municipal beach (a short distance from the motel where AAPA's 1966 convention was held), I was more than bit nervous. I was sure every eye would be focused on my lopsided chest.

Much to my relief, the beach watchers were watching the bikinis, as usual, and if anybody was curious about my bulge, the stares weren't obvious. Swimming I've always enjoyed, and the almost daily regimen in the sun has left me feeling better than ever.

I was back at work three weeks after the operation, still feeling twinges when I'd open heavy doors and getting tired in mid-afternoon. But each week that passed, the stronger I felt.

Now, as I stroke through the bay water, then bask in the sun, I think how fortunate I was that a doctor friend just happened to call the paper one day.

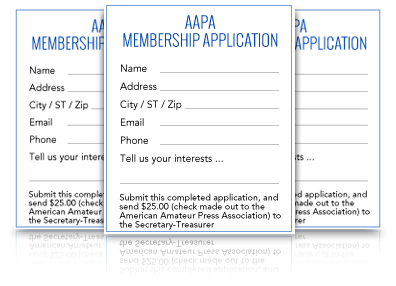

JOIN AAPA!

Become A Member!

Amateur journalism is a unique activity. Amateur journalists publish journals on paper & online & come from many perspectives: from deluxe letterpress printed journals, to Xeroxed newsletters, to artistically designed cards and ephemera. We embrace the spirit of being amateurs – loving what we do for pure joy and not financial gain – while creating top quality journals, zines, and homemade publications.

Amateur journalism is a unique activity. Amateur journalists publish journals on paper & online & come from many perspectives: from deluxe letterpress printed journals, to Xeroxed newsletters, to artistically designed cards and ephemera. We embrace the spirit of being amateurs – loving what we do for pure joy and not financial gain – while creating top quality journals, zines, and homemade publications.

Members receive ...

- The monthly bundle mailed via the postal service

- Access to the website and e-journals

- e-mailed updates

- Ability to publish your stories on AAPA

|

|