Ernestine's Beauty Parlor

Ernestine’s Beauty Parlor

Every two months grandma Etta had a hair appointment. Just about the time the hair began to relax from the last permanent so that she lost some of the severity about her head, she asked his mother to take her to town, and she came back looking as if she had clamped on a steel wool helmet. At seven or eight years of age he began to marvel at such changes in the women around him: he’d see grandma in the morning over coffee with tufts of hair liberated from their curly prison, but when he returned from school that afternoon those tufts were subdued back into their chain-mail bondage. At first, he imagined the transformation was accomplished by the combs and brushes he had seen mama use, but mama’s hair always seemed free and wispy after using those tools. After a day of her cleaning, cooking, and patching his scraped elbows, her hair would be like the bandy’s feathers after an upset in the chicken yard. Before his father returned home and as the daylight faded, she would sit before the mirror and brush her hair. He especially noticed this ritual during winter, when dusk came early and a crisp blue norther spilled down from the Hill Country rim. In the glow of the bare electric bulb, steam from her nearby coffee cup spiraled upward and electricity crackled between the brush and her hair, sometimes raising sparkles and always leaving wisps of her hair to dance in silhouette against the light. So in his imaginings about grandma’s hair metamorphosis, he thought combs and brushes would not be enough. And they weren’t. He learned that when summer came during his eighth year, and he made the journey with mama and grandma Etta to Aunt Ernestine’s beauty parlor.

Aunt Ernestine, grandma’s sister, lived nearly clear across San Antonio, so they had to ride the bus through town and transfer several times before they got to her place. They caught the Broadway line across the street from the entrance to the San Antonio airport on Loop 13. Here on the outskirts of the city, a few houses and businesses, such as Skipper’s Diner across the way, were scattered over the pastures, cornfields, and mesquite woods. The bus stop was familiar territory because this was where the children of the vicinity gathered to catch the bus to school. Although during the school year they rode the regular transit system bus, few adults dared the ride with the thirty or so kids on the 7:00 am run. But this summer day, the first time he went with grandma Etta and mama to Aunt Ernestine’s, he was the only child on the bus. The aroma of eggs and percolating coffee hung around Skipper’s across the highway as it did every morning, and when the bus arrived and they boarded, the driver’s open thermos blended with the outside world.

The only other passenger was a suited man, perhaps a traveler who could not afford a taxi and had boarded at the airport terminal. That man sat behind the driver and exchanged a few comments until the bus grew crowded as it headed into the city. Broadway is one of the major north-south thoroughfares into San Antonio, and the stops became more frequent as they neared downtown. Early boarders seemed like them, having some early business in town or perhaps going to visit friends or family in other parts of the city. But some were going to work, for they had their lunch boxes or tool boxes. Several Mexican women boarded at the Cementville gate, entrance to the large quarry and cement factory of Alamo Portland Cement. Some rode a few blocks into Alamo Heights, an affluent suburb, and some rode farther to their jobs as cooks, maids, custodians. The smell of coffee still in his head, he imagined they were a mixture of café and café con leche, from the dark brown of a thin stream of coffee to the rich khaki of creamed coffee. A few stops later a man in khakis got on, sat besides one of the Cementville women, said “Buenos días,” and poured coffee into the lid of his thermos. The boy sat enchanted in the colors and fragrances of coffee, the soft murmurs of Spanish, the stop-go rhythm of the bus. The man in khaki wore a coarse-weave straw hat and a tightly-rolled bandana around his neck. Most of the women wore head scarves with only a few strands of their black hair loose about their foreheads or cheeks. One woman’s braid curled from under her head scarf over her shoulder and across her bosom. Its black glistened against the pale blue of her blouse.

More passengers boarded and took the places of these earlier riders. A woman wore a striped pink waitress uniform; a man wore the military cut uniform of maroon like that of a doorman or elevator operator. A mother with a girl his age and a younger boy crammed into one bench. The girl and he looked at one another as children do in a roomful of adults; then they gazed away at the passing buildings of the city.

Mama, grandma, and he disembarked when the bus turned off Broadway to wend its way through the one-way streets of the center of San Antonio. They walked a block east on Houston toward Alamo Plaza to catch the next ride that would take them away from downtown. The sidewalks were not crowded: a few people walking to their work, some shops or offices just opening, clerks rolling displays into wide entrances or taping signs announcing bargains on the windows. At the Plaza they continued walking abreast of the Alamo grounds with the Cenotaph to the Heroes of the Alamo between. They waited at the stop across from Joske’s Department Store on Alamo and Commerce. Mama and grandma talked about some dresses in Joske’s windows, but he wished it were Christmas so that the window would be full of the electric train display of a Christmas wonderland. The aroma of coffee floated from the café behind them.

They snaked their way south and east from downtown. Along South Presa, the smells of tamales and barbacoa slipped into the open windows of the bus and nearly as quickly were replaced with the fumes of the traffic. Spanish competed with English on the signs outside businesses. They changed buses several times, and on each were only a few people. Once they passed a bus returning toward downtown; it was filled with passengers on their way to work or business in the city. He guessed that only a few people were going to Aunt Ernestine’s beauty parlor.

Although he had never been to Aunt Ernestine’s, he was surprised his mother said that they were there when they disembarked in front of a small block-long shopping strip on Highland Avenue. He had connected Aunt Ernestine with a house, as he pictured grandma Etta and most women of his family; he did not connect them with places of business. Later that day he discovered that Ernestine did indeed live in a house–only a few blocks up the avenue, with her son’s family; but every weekday she walked down the street to her shop to beautify the women on the southeast side of San Antonio. But as they stepped down from the bus and Mama motioned toward the far end of the shopping strip, he saw “Ernestine’s Beauty Parlor” neatly lettered on her shop window and somehow felt that it was appropriate.

They passed from the bus stop across the small strip of parking spaces before the stores onto the sidewalk that fronted them. A Piggly-Wiggly grocery store dominated the businesses, running from the corner to the middle of the block. After that were small retailers, a fix-it shop, an insurance agent, and next to it, Aunt Ernestine’s. They walked slowly because grandma Etta could not go any faster, so they had a long time to swim in the odd mixture of odors–half coffee, half the ammoniac beauty parlor smells–that seeped from the parlor’s open door up the sidewalk to the insurance agent’s door, where they dove into the odors.

Inside, Aunt Ernestine was already busy with two women. He assumed it was Aunt Ernestine although he could not remember ever seeing her before that moment. She reminded him of Grandma Etta, short and stocky and wrinkled with deep blue eyes. And when she saw them and said “Guten Morgen. Wie gehts?” followed by “How are you?” she sounded exactly like Grandma. The two customers raised their eyes from magazines. Behind one stood Aunt Ernestine holding a strand of hair in one hand and a curler in the other. The woman’s head was halfway covered with completed curlers. The other woman had her head under a drier, which looked like some outer space apparatus he had seen in one of the pulp magazines Grandpa read. As Grandma, Mama, and Aunt Ernestine hugged and marveled at how big he was getting, he took in the shop. It was a rectangle with large plate-glass windows on either side of the entry door. Ernestine’s was written in large red trimmed black letters on one window; Beauty Parlor, on the other. The words were backwards, and he played a quick optical game with the t’s in Ernestine’s and on a Butter Krust bread truck parked back toward the Piggly Wiggly. Three large mirrors covered one of the long walls and made the room seem twice as large. A clock that showed 9:30 was slightly off center above the middle mirror. A few vinyl-covered chairs surrounded a low table with magazines and a couple of coffee cups under the mirrors. On the other long wall were two deep sinks and cabinets, with some drawers half open and counter tops covered with gadgets and devices he had never seen before. High on the wall was a tapestry of a scene from Spanish colonial San Antonio. Around a fountain in the center of a courtyard were several figures, mostly idle young men but a few Indian servants. One young man strummed a guitar and all the young men looked up toward a balcony to the left of the scene where a señorita with luxuriant black hair leaned almost weightlessly against the rail. He supposed the young woman’s hair was the point of the tapestry being in the shop. But none of the women in the room had a similar head of hair. In fact, all of their hair could have been thrown together and he doubted it would have equaled the mass on the señorita’s head.

His eight year old curiosity was trying to decipher all of this while also wondering if on the magazine strewn table were any good magazines like Grandpa’s Weird and Popular Mechanix and while, all along, the smell of neutralizer sniped at any other sensation. Years later, he read Proust, and so when he walks past a hair salon and gets a whiff of that odor, a vision of the dark haired señorita of the tapestry and all the details of Aunt Ernestine’s Beauty Parlor paralyzes him for a moment, but then Proust and his madeleine’s assert themselves as the editor of his memory.

However, at eight years of age, the delicacies of Proust and memory did not exist for him, but the nauseating smell of the neutralizer and the tapestry’s incongruity in that room–although he could not have articulated his reaction as such–were quickened to his entire world. Had the lovely Spanish maiden–he assumed she was lovely because of the idle young men’s rapt attention and the flowing coiffure, but her actual face was not clearly rendered in the tapestry– had the lovely maiden just returned from some colonial San Antonio equivalent of Aunt Ernestine’s, where she had gone through the process Aunt Ernestine was now performing on those two ladies? Had the beautiful Maria or Consuelo’s hair been doused with that wretched smelling concoction? Did women have to submit to this odor to be satisfied with their hair? If so, why? Were they able to endure more offensive odors than men? Or were they engineered differently so that the odor was not sickening? Was that smell an acquired taste as he had heard adults speak about beer and he had learned about okra? So does that happen to girls who begin having their hair treated at beauty salons? Perhaps, the fumes from the beauty potion chemicals were making him light-headed, but these questions sprang to mind when, just as incongruous and incorporeal as the odor, a voice from beyond the door that centered the rear wall of the shop asked, “Does anyone want coffee?”

The voice was as enchanting as the señorita’s hair. It lilted. He somehow thought it should follow the question with the lyrics of “Jole Blon” mingling with Harry Choates’ fiddle, for it was a Cajun voice. He had begged many a nickel from his father to play that song on the jukebox at Tate Mueller’s Anchor Bar and Barbeque down the road from their house, and he registered the Cajun inflection in his head as much as he did the German he heard among family and the Spanish he heard in the neighborhood and on the bus as this morning. So he knew this bonne femme who offered coffee from the backroom was Cajun, but who was she? And then Madelyn entered with a tray of steaming coffee cups.

Later that day he learned that Madelyn was Aunt Ernestine’s daughter-in-law. Her son Albert had met Madelyn while stationed at Ft. Polk and they had married after the war. A decade later he saw a painting of Madelyn in a book on the Pre-Raphaelites. Or her spiritual twin. The woman who emerged from the backroom with wisps of coffee steam spiraling in her auburn hair was the image of Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s Astarte Syriaca. Her hair was even more luxuriant than the tapestry señorita’s. It was real and had subtle depth one could hide in. At eight, he did not understand the gazes of all the idle young men in the tapestry, and even a decade later he did not fully understand Rossetti’s yearning in his portrait.

But he did sense the hair. Somehow the coffee that had been the flavor of the air they had been breathing all morning was intensified and became the fragrance of Madelyn’s hair. It was headier, as if the essence of jungle mornings were ground with the beans. The ozone smell of approaching rain mixed with the humus, vines, and skittering lizards of the coffee plantation. Even the nauseating smell of the permanent solution was overpowered. And although she was still at the rear of the room fifteen feet away, when she turned and bent toward grandma Etta to give her a cup, that jungle of auburn hair seemed to brush his nose. He reached out to grasp it and quickly drew back his hand, glad that all eyes were on Madelyn. It was a jungle of hair, not because of unkempt nature but because of the richness, the energy that ran under the surface. It had the sheen of mama’s hair in those late afternoon brushings, and a few strands almost lifted as Madelyn moved around the shop. But unlike the ephemeral lightness of mama’s brunette hair, this auburn hair had a mysterious weight despite the way it refused to lie silently around her head. All the other women had hair that clung fiercely or lay limpidly –either naturally or by design, as with grandma’s permanent. Madelyn’s hair was incongruous just as the tapestry and the tapestry’s señorita in that shop. The tapestry was a curiosity, but Madelyn–or her hair–was a threat.

After serving grandma and mama, the two other customer, and Aunt Ernestine, Madelyn turned toward the boy. “And here is the big man who needs his coffee?” She asked and placed a cup half-full of coffee on the table before him. The coffee steamed up into his face, so strong that the last faint memory of the permanent solution’s burning of his nose disappeared. “Do you want it black or with some cream?” A strange urge made him almost say “Black,” although he had never had straight coffee and he knew he preferred the rich cream. The pint of cream on the tray was about three-quarters full and thin streaks of dribble curved over the bottle rim and serpentined down to the raised letters on the side of the bottle. He licked his lips as if willing those streaks onto his tongue. “With cream,” he said. Madelyn’s brown eyes smiled and she filled the cup, the brown of the liquid fading from the dark of her eyes to the tan of her skin. She put in two spoonfuls of sugar and stirred, loosening her hair with the movement so that a thick strand dropped over one eye. The suddenness of the hair dropping over that sparkling eye caught his breath, and when he inhaled an indistinct needle of permanent solution scratched behind his eyes. He took a big sip of the coffee and buried his nose into the emptiness left.

Recent Stories

- July 03, 2020 :: Greg McKelvey

Summer 2020 Ink Zone (#176) - April 07, 2020 :: Marey Barthoff

Oh Dear AAPA'ers - June 30, 2019 :: Clarence Wolfshohl

June 2019 AAPA Miscellany - September 25, 2018 :: Clarence Wolfshohl

Boar Finds a Comfortable Home - September 05, 2018 :: Greg & Sally McKelvey

Fall 2018 Ink Zone (#156) - August 01, 2017 :: Clarence Wolfshohl

July 2017 AAPA Miscellany - July 15, 2016 :: Clarence Wolfshohl

June 2016 AAPA Miscellany - January 29, 2015 :: Dave Griffin

AAPA MIscellany Premiers - February 26, 2015 :: Clarence Wolfshohl

April 2015 AAPA Miscellany - June 22, 2015 :: Clarence Wolfshohl

June 2015 AAPA Miscellany - June 22, 2015 ::

About E-Journals - June 19, 2015 :: Clarence Wolfshohl

Ernestine's Beauty Parlor - February 11, 2015 :: Delores Zillmer Miller

PICKING STONES AND BUILDING BARNS - April 28, 2015 :: Clarence Wolfshohl

NEVSKY PROSPECT - February 26, 2015 :: David Griffin

MEASURE - February 11, 2015 :: Sandra Gurev

HOME - February 02, 2015 :: Clarence Wolfshohl

MY LIFE WITH TOM - January 27, 2015 :: Sandra Gurev

SHE’S TROUBLE WITH A CAPITAL T - November 25, 2014 :: David Griffin

OLD SHOES - October 15, 2014 :: Sandra Gurev

THE MADCAP ADVENTURES OF ELIEZER GUREVITCH - August 13, 2014 :: Delores Miller

HUCK AND PUCK - July 26, 2014 :: David Griffin

Golden - July 11, 2014 :: Peter Schaub

The Isle of Devils - July 02, 2016 ::

AAPA E-Journal Listings - June 27, 2014 :: David Griffin

ANTHROPOLOGY

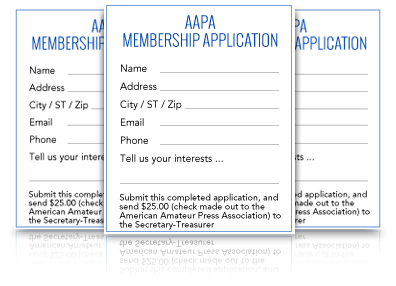

JOIN AAPA!

Become A Member!

Amateur journalism is a unique activity. Amateur journalists publish journals on paper & online & come from many perspectives: from deluxe letterpress printed journals, to Xeroxed newsletters, to artistically designed cards and ephemera. We embrace the spirit of being amateurs – loving what we do for pure joy and not financial gain – while creating top quality journals, zines, and homemade publications.

Amateur journalism is a unique activity. Amateur journalists publish journals on paper & online & come from many perspectives: from deluxe letterpress printed journals, to Xeroxed newsletters, to artistically designed cards and ephemera. We embrace the spirit of being amateurs – loving what we do for pure joy and not financial gain – while creating top quality journals, zines, and homemade publications.

Members receive ...

- The monthly bundle mailed via the postal service

- Access to the website and e-journals

- e-mailed updates

- Ability to publish your stories on AAPA

|

|