HOME

On a blustery December night in Rochester, New York in 1979 my husband and I headed to the Rochester International Airport. We planned on meeting with other members of our synagogue, Temple Sinai, to greet a Laotian family whose father had escaped after six years in a Vietnamese concentration camp and rejoined with his wife and six children at a refugee camp in Thailand.

On a blustery December night in Rochester, New York in 1979 my husband and I headed to the Rochester International Airport. We planned on meeting with other members of our synagogue, Temple Sinai, to greet a Laotian family whose father had escaped after six years in a Vietnamese concentration camp and rejoined with his wife and six children at a refugee camp in Thailand.

Our small group came prepared with shopping bags of coats, boots, mittens, scarves and hats to fit two adults and six children ranging in age between fourteen and six. Our synagogue sponsored the family. Our commitment entailed finding an apartment for them on a bus line, providing furniture and kitchen ware, enrolling the children in school, and obtaining Medicaid and Aid to Dependent Families, helping them to find jobs, enrolling them in English language classes and providing friendship. It was a tall order but we had such a large group of enthusiastic volunteers willing to share the responsibilities.

We were told that the family would be arriving from a refugee camp in Thailand where they had lived for 1-2 years. Since we anticipated them arriving in lightweight clothing not suitable for Upstate New York winters, we were ready for them with the warm outer clothing. Much to our surprise they came off the plane fully dressed for snowy weather. We later learned that the Jewish Federation outfitted them during a flight stopover in San Francisco. It was the first of many surprises.

A small group of people from the Rochester Laotian community were also there to greet them. They were the first to welcome them in the only language they knew. We followed their actions by bowing our heads slightly while bringing our hands together as if in prayer.

The Chanthachakvong family’s consists of Soubahn and his wife, Somchith and their children Olyvan, Vilylak, Thippiphone, Nu, Phonketkeo, and Mee. They carried wide smiles on their faces and gave us hearty hugs. We were pleased that they were so friendly and happy to see us.

Preceding the family’s arrival in New York, the Jewish Federation sent us handouts about the cultural practices of Laotians. For example, we were advised to never touch them on their heads or shoulders as it was considered a sign of disrespect. Furthermore we learned that we might be receiving Hmong refugees who live in the mountainous area of Laos. They are an ethnic group who speak a different language, live in communal homes and have no written language. They are unaccustomed to indoor plumbing, heating, and refrigeration. In short, we had no idea about the background of the family we were to welcome.

After extended greetings at the airport, we climbed into several cars to take the Chanthachakvong family to their three bedroom fully furnished apartment on Hickory Street in Rochester’s southwest wedge. As we walked from our car to the apartment, the snow was glistening and crunchy under our feet. I scooped up a handful throwing it in the air. They were excited with their first glimpse of the pure white snow and enjoyed placing it against their cheeks and tasting it.

We entered the apartment and judging by their facial expressions, they were pleased with their new home. I noticed that no one in the family removed their winter jackets. The temperature registered at about 70 degrees, cold for people accustomed to a tropical climate.

Unable to communicate with words, I decided to introduce the kitchen and bathroom through sign language and exclamations. I jumped to the conclusion that the family came from the ethnic Hmong that we had read about and thereby assumed they had no knowledge of refrigeration, stove burners, flush toilets and showers. I ushered them into the small kitchen and I opened the refrigerator showing them assorted foods that would last them until a volunteer took them grocery shopping. I pretended to shiver while rubbing my arms and produced a sound that resembled “brrr brrr.” As I reached my arm into the refrigerator I called out, “Cold, cold!” So far, so good. Then I demonstrated the gas stove. I turned on the burner waving my hand close to it, pulling it back sharply and showing distress. “Hot, hot, I exclaimed!” Next stop, the bathroom. I stopped short of actually sitting on the toilet seat with my jeans rolled down around my ankles. I did, however, flush the toilet and showed how to turn on the shower and faucet. My eyes probably sparkled with the knowledge that I was being helpful.

Year’s later we were talking to one of the children about their first night in Rochester. I learned for the first time that the family lived an upper class life enjoying shopping for furniture in Paris, having a nanny, a car, travel and all the trappings of a comfortable life style. Soubahn had been employed by the United States Army in a high paying position. My face flushed when I recalled my assumptions from so long ago about their lives in Laos.

In 2006 we drove to Atlanta to visit our friends of almost thirty years who moved there in 1993 to escape the cold. We talked at length about my early assumptions and enjoyed a good laugh together. I wish I had asked them if they had found my behavior amusing or puzzling or even more likely strange.

Today the Chanthachakvong family is the epitome of the American success story. Through hard work, a strong family and a Laotian community that provided much support, they have achieved college educations for the four younger children, beautiful homes in Atlanta and Rochester and a comfortable life style. We have been enriched by their friendship.

copyright 2015 Sandra Gurev

Sandy Gurev is a wife of fifty-one years and mother of two sons and four grandchildren. Sandy was an elementary school counselor prior to retiring to Williamsburg, VA nine year’s ago from Rochester, NY. Her volunteer work includes providing lunch to cancer patients and fitting women with wigs after they have lost their hair. Playing competitive duplicate bridge and belonging to two book clubs rounds out her time. Within the past two years she has written a memoir for her grandchildren and a couple of articles for the American Amateur Press Association. Sandy found that writing helped to reduce her perception of pain while she was awaiting back surgery.

Share:

Recent Stories

- July 03, 2020 :: Greg McKelvey

Summer 2020 Ink Zone (#176) - April 07, 2020 :: Marey Barthoff

Oh Dear AAPA'ers - June 30, 2019 :: Clarence Wolfshohl

June 2019 AAPA Miscellany - September 25, 2018 :: Clarence Wolfshohl

Boar Finds a Comfortable Home - September 05, 2018 :: Greg & Sally McKelvey

Fall 2018 Ink Zone (#156) - August 01, 2017 :: Clarence Wolfshohl

July 2017 AAPA Miscellany - July 15, 2016 :: Clarence Wolfshohl

June 2016 AAPA Miscellany - January 29, 2015 :: Dave Griffin

AAPA MIscellany Premiers - February 26, 2015 :: Clarence Wolfshohl

April 2015 AAPA Miscellany - June 22, 2015 :: Clarence Wolfshohl

June 2015 AAPA Miscellany - June 22, 2015 ::

About E-Journals - June 19, 2015 :: Clarence Wolfshohl

Ernestine's Beauty Parlor - February 11, 2015 :: Delores Zillmer Miller

PICKING STONES AND BUILDING BARNS - April 28, 2015 :: Clarence Wolfshohl

NEVSKY PROSPECT - February 26, 2015 :: David Griffin

MEASURE - February 11, 2015 :: Sandra Gurev

HOME - February 02, 2015 :: Clarence Wolfshohl

MY LIFE WITH TOM - January 27, 2015 :: Sandra Gurev

SHE’S TROUBLE WITH A CAPITAL T - November 25, 2014 :: David Griffin

OLD SHOES - October 15, 2014 :: Sandra Gurev

THE MADCAP ADVENTURES OF ELIEZER GUREVITCH - August 13, 2014 :: Delores Miller

HUCK AND PUCK - July 26, 2014 :: David Griffin

Golden - July 11, 2014 :: Peter Schaub

The Isle of Devils - July 02, 2016 ::

AAPA E-Journal Listings - June 27, 2014 :: David Griffin

ANTHROPOLOGY

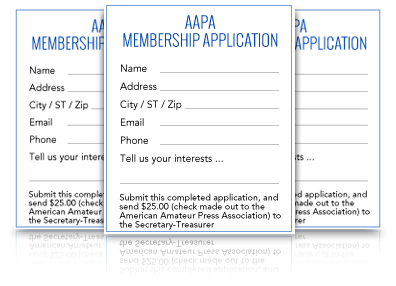

JOIN AAPA!

Become A Member!

Amateur journalism is a unique activity. Amateur journalists publish journals on paper & online & come from many perspectives: from deluxe letterpress printed journals, to Xeroxed newsletters, to artistically designed cards and ephemera. We embrace the spirit of being amateurs – loving what we do for pure joy and not financial gain – while creating top quality journals, zines, and homemade publications.

Amateur journalism is a unique activity. Amateur journalists publish journals on paper & online & come from many perspectives: from deluxe letterpress printed journals, to Xeroxed newsletters, to artistically designed cards and ephemera. We embrace the spirit of being amateurs – loving what we do for pure joy and not financial gain – while creating top quality journals, zines, and homemade publications.

Members receive ...

- The monthly bundle mailed via the postal service

- Access to the website and e-journals

- e-mailed updates

- Ability to publish your stories on AAPA

|

|