THE MADCAP ADVENTURES OF ELIEZER GUREVITCH

My father-in-law, Elias Gurev, was fifty-nine when I met him. He was tall, broad framed with a thick thatch of iron grey hair. His legs seemed mismatched with his body as they were thin. They didn’ seem like they could support his broad chest. I never got to know him well due to a signicant permanent hearing loss from German measles at age sixteen. Our conversations were monologues and my attempts to ask questions went unanswered. His loss of hearing led to some degree of paranoia thinking people were talking about him.When our sons were born in the late 60’s, their grandfather would take Greg or Keith on his knee calling, “Come boychick, come and sit on grandpa’s lap.” They enjoyed being bounced on his knee and gave him their complete attention when he regaled them with stories from long ago. His stories almost always touched on his heroism.

For instance, he told us about riding with Pancho Villa on his trusty mule, Rosita. I listened in on his monologue with the boys and envisioned him wearing a colorful serape, sombrero askew riding hard through mountain canyons calling to Rosita, “Andele!” The sunsets were brush stroked in lavender, mango, and magenta.

Other stories revolved around riding with the Cossacks through the Russian Steppes or as a sidekick to Genghis Khan. Some of his leaders were ruthless barbarians but it didn’t seem to matter. Adventure abounded in his stories. Our boys sat with rapt attention , their eyes growing wider with disbelief with each ensuing tale.

One day my father-in-law became serious and his story took on a decidedly solemn tone. He described a memory of a time when he was about twelve. He lived in an expansive richly decorated home with his parents and sister in some unknown country. He spoke lovingly of running his fingers over the ivory keys of the family’s grand piano. Then he said, “We had to leave and I knew that I would never see it again.” Again his hearing loss prevented me from asking for more details, questions that I yearned to ask.It wasn’t until 2012 that I began to get answers to my questions. I came across a yellowed creased petition requesting citizenship to the British protectorate of Palestine. The year was 1930.

I learned that my father-in-law was born into a Jewish family in Theodosia, Crimea. His father had a well paying government position working for the Czar. His family had enjoyed a comfortable upper middle class lifestyle. Their lives changed abruptly when an empathetic Cossack calvaryman paid an unannounced visit. He had learned that the Czar’s army was planning to launch a pogrom against the Jews of Theodosia. The man urged them to leave immediately. They needed to get on the first ferry to neighboring Turkey. The family hastily piled documents, photos, perhaps a pair of silver candlesticks for the sabbath onto sheets and escaped through the cover of night. His father managed to go to a bank before leaving only withdrawing enough money as he could without arousing suspicion. They fled their home leaving the door wide open and safely escaped by ferry. Most of the remaining Jewish residents were terrorized and killed by the army.

Turkey was not much better. This time they may have been persecuted by a different aggressor but the reason remained the same. They were Jews. I learned through my sister-in-law, Sylvia, that she remembers her dad talking about the day of his Bar Mitzvah which occurred shortly after the family moved to Turkey. He recalled that following his Bar Mitzvah he was carried on the shoulders of the men through the streets, a long standing tradition.

Eventually the family migrated to Palestine by ship carrying British passports. I don’t know the circumstance of how the passports were obtained, probably illegally. Jews were not welcome there as well. Their new enemies were the Arabs. The British government, no friend of the Jews, did not want the hassle of dealing with the politics of the region. They provided weak protection to the settlers.

As more Jews from Europe fled to Palestine, anger against them grew and they formed groups to protect themselves. One well known group was the Haganah. It was a Jewish paramilitary organization, in what was the British Mandate of Palestine from 1920 to 1948. Believing that they could not rely on the British for protection from local Arab gangs, the Jewish leadership created the Haganah to protect Jewish farms and kibbutzim during the 1920’s. Following the 1929 Palestine riots, the Haganah’s role changed dramatically. It became a larger organization acquiring foreign arms and going from an untrained militia to a capable underground army.

As more Jews from Europe fled to Palestine, anger against them grew and they formed groups to protect themselves. One well known group was the Haganah. It was a Jewish paramilitary organization, in what was the British Mandate of Palestine from 1920 to 1948. Believing that they could not rely on the British for protection from local Arab gangs, the Jewish leadership created the Haganah to protect Jewish farms and kibbutzim during the 1920’s. Following the 1929 Palestine riots, the Haganah’s role changed dramatically. It became a larger organization acquiring foreign arms and going from an untrained militia to a capable underground army.

The yellowed document I wrote about earlier revealed the applicant as Eliezer Gurevitch formerly Asher Segal which may have been an alias that he had once used. My sister-in-law filled in the missing pieces of the puzzle, a story my husband knew little of. I had an opportunity to share as well because I had always heard that my father-in-law was from the Republic of Georgia.

I learned that my father-in-law worked for the Haganah. He secreted guns in the luggage compartment of Palestinian tour buses while doubling as a driver for a Palestinian touring company. He and his cousin did this risky work until it became too dangerous. His mother borrowed money to pay for a visa and and roundtrip passage to the United States. He sailed to New York harbor arranging to meet with his American family who had emigrated to Buffalo, New York. During his brief stay in Buffalo, family in Cleveland, Ohio introduced him to four unmarried sisters. He had a choice of marrying any one of them!

Their father judiciously allowed his daughters the right to refuse a proposal if any one of them had strong feelings against the suitor. He reminds me of Tevye from ” Fiddler on the Roof who allowed two of his daughters to marry for love. Unheard of during the early years of the twentieth century. He chose my mother-in-law, Edna, because she laughed at his jokes and had a good sense of humor. She expressed her desire to marry the handsome young man. After a two week courtship, they married.

He was twenty-four and she thirty-five. She was advised by her sisters not to talk about her age. She never told him that she was eleven year’s older but he knew how old her siblings were and that she was the oldest of six. Years before he died, my father-in-law took my husband and me into his confidence and said, “Mama doesn’t know that I know how old she is. That is to remain our secret.” Only after his death did she learn.

She did not apply for Social Security when it was possible for her to do so because she didn’t want her husband to know that their marriage had begun with a lie. She ruefully told the family, ” He should have told me that he knew. I could have collected Social Security ten years earlier!”

Three weeks after marrying Elias, his visa expired and he reluctantly returned to Palestine. During the spring of 1931, he learned that he was going to become a father. Baby Sylvia was born on January 21, 1932. Her dad was able to return to the states a week before her birth. much to everyone’s relief.

To the average onlooker my father-in-law’s life must have seemed monotonous. He worked seven days a week during the early years of their marriage operating a gas station and had little time and money for fun and leisure. On national holidays he managed to pile Sylvia and six small children from the neighborhood into his coupe and head for Euclid Beach Park on Lake Erie. He bought tickets for all the children to go on the rides and treated them to ice cream. He treasured those moments as did his daughter, Sylvia.

Life was hard for the Gurev family and millions of other young couples starting out as the Great Depression deepened until the advent of World War Two. The newlyweds moved into Edna’s parents’ home. Seven adults shared a three bedroom house. The sisters-in-law slept on an enclosed back porch which was freezing in the winter. When Sylvia no longer slept in a crib, she slept in the dining room on a cot. She got no rest until the adults went to bed. She never called her dad “daddy” until she was twelve probably because she rarely saw him as he went to work before she awakened and worked until 10:30 at night.

Sylvia remembers her father as honest, brave, polite and proud. He was fluent in six languages, had an excellent education since his father worked for the czar for the first twelve years of his life but circumstances including the effect of measles prevented him from getting a a job that required his intellect. He loved being around children and telling whoppers. His imagination allowed him to roam far and wide risking life and limb in death defying escapes. In his late sixties, he and my mother-in-law took a long dreamed for trip to Israel meeting relatives in Tel Aviv and touring the country. They somehow managed to walk up the crude steps at Masada to pay homage to those martyrs who died there long ago.

My father-in-law shortened his name some years later to Elias Gurev, a name I personally prefer because spelling my last name to those who don’t know me would no doubt be more problematic than it already is.

Elias was not one to be bitter over all the family had lost during his younger years. His joy came from his family and customers he befriended at his local gas station. He told his daughter, Sylvia, that he had felt some momentary disappointment when the doctor told him he had a daughter but he could swap her for a boy if he remained unhappy. They both had a good laugh knowing that once Sylvia nestled is her daddy’s arms, he would never let her go.

They went from one child to having Harold six year’s later and my husband, Jerry, four years after Harold’s birth. Jerry’s birth was remarkable in that his mother was forty five when he belted out his first lusty cry.

Elias’s tales will linger for as long as his children and grandchildren keep them alive.

Copyright 2014 by Sandra Gurev

Sandy Gurev is a wife of fifty-one years and mother of two sons and four grandchildren. Sandy was an elementary school counselor prior to retiring to Williamsburg, VA nine year’s ago from Rochester, NY. Her volunteer work includes providing lunch to cancer patients and fitting women with wigs after they have lost their hair. Playing competitive duplicate bridge and belonging to two book clubs rounds out her time. Within the past two years she has written a memoir for her grandchildren and a couple of articles for the American Amateur Press Association. Sandy found that writing helped to reduce her perception of pain while she was awaiting back surgery.

Share:

Recent Stories

- July 03, 2020 :: Greg McKelvey

Summer 2020 Ink Zone (#176) - April 07, 2020 :: Marey Barthoff

Oh Dear AAPA'ers - June 30, 2019 :: Clarence Wolfshohl

June 2019 AAPA Miscellany - September 25, 2018 :: Clarence Wolfshohl

Boar Finds a Comfortable Home - September 05, 2018 :: Greg & Sally McKelvey

Fall 2018 Ink Zone (#156) - August 01, 2017 :: Clarence Wolfshohl

July 2017 AAPA Miscellany - July 15, 2016 :: Clarence Wolfshohl

June 2016 AAPA Miscellany - January 29, 2015 :: Dave Griffin

AAPA MIscellany Premiers - February 26, 2015 :: Clarence Wolfshohl

April 2015 AAPA Miscellany - June 22, 2015 :: Clarence Wolfshohl

June 2015 AAPA Miscellany - June 22, 2015 ::

About E-Journals - June 19, 2015 :: Clarence Wolfshohl

Ernestine's Beauty Parlor - February 11, 2015 :: Delores Zillmer Miller

PICKING STONES AND BUILDING BARNS - April 28, 2015 :: Clarence Wolfshohl

NEVSKY PROSPECT - February 26, 2015 :: David Griffin

MEASURE - February 11, 2015 :: Sandra Gurev

HOME - February 02, 2015 :: Clarence Wolfshohl

MY LIFE WITH TOM - January 27, 2015 :: Sandra Gurev

SHE’S TROUBLE WITH A CAPITAL T - November 25, 2014 :: David Griffin

OLD SHOES - October 15, 2014 :: Sandra Gurev

THE MADCAP ADVENTURES OF ELIEZER GUREVITCH - August 13, 2014 :: Delores Miller

HUCK AND PUCK - July 26, 2014 :: David Griffin

Golden - July 11, 2014 :: Peter Schaub

The Isle of Devils - July 02, 2016 ::

AAPA E-Journal Listings - June 27, 2014 :: David Griffin

ANTHROPOLOGY

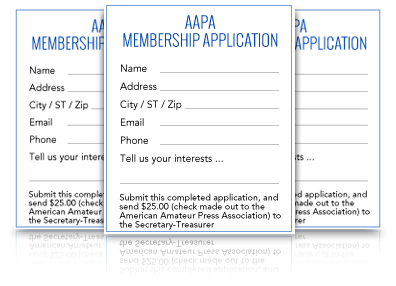

JOIN AAPA!

Become A Member!

Amateur journalism is a unique activity. Amateur journalists publish journals on paper & online & come from many perspectives: from deluxe letterpress printed journals, to Xeroxed newsletters, to artistically designed cards and ephemera. We embrace the spirit of being amateurs – loving what we do for pure joy and not financial gain – while creating top quality journals, zines, and homemade publications.

Amateur journalism is a unique activity. Amateur journalists publish journals on paper & online & come from many perspectives: from deluxe letterpress printed journals, to Xeroxed newsletters, to artistically designed cards and ephemera. We embrace the spirit of being amateurs – loving what we do for pure joy and not financial gain – while creating top quality journals, zines, and homemade publications.

Members receive ...

- The monthly bundle mailed via the postal service

- Access to the website and e-journals

- e-mailed updates

- Ability to publish your stories on AAPA

|

|