The Isle of Devils

Beautiful Bermuda was on nobody’s bucket list in the 1600s. Named for Juan Bermudez, who discovered them about 1505, the islands were feared by the Spanish and Portuguese who rode the Gulf Stream from the Caribbean to Europe. The reefs surrounding the islands are treacherous, making a purposeful entry to harbor all but impossible in that era. The screeching cahow birds would have sounded to superstitious sailors like wailing demons. They called the place the “Isle of Devils”.

Sea Venture was the flagship of the relief fleet sent from England to Jamestowne in 1609. Hit by a hurricane, six battered vessels made it into Jamestowne with most of the provisions spoiled. The Sea Venture carried the senior leaders and wrecked on Bermuda. Even as the gunwales were awash, Captain Newport, Admiral Somers and Governor Gates must have been wondering which fate was better: drowning at sea or being wrecked on that abhorred shore.

Unlike those shipwrecked Jamestowne settlers, Connie and I arrived safe and dry in Bermuda with our friends on a lovely April day. Bermuda is not only pink coral beaches, gentle turquoise waves, and great golf courses. We spent the next week meeting interesting people, learning about Bermuda’s history, and sampling the local favorite, the “dark and stormy” made with Bermuda dark rum. Our interest in Bermuda started with our interest in Historic Jamestowne where the recent discoveries are showing the connections between the earliest British settlements in America. For example, Bermuda limestone was found inside the Jamestowne fort site in a 1610 context. This was ballast used in the new ships built by the Sea Venture survivors.

Unlike those shipwrecked Jamestowne settlers, Connie and I arrived safe and dry in Bermuda with our friends on a lovely April day. Bermuda is not only pink coral beaches, gentle turquoise waves, and great golf courses. We spent the next week meeting interesting people, learning about Bermuda’s history, and sampling the local favorite, the “dark and stormy” made with Bermuda dark rum. Our interest in Bermuda started with our interest in Historic Jamestowne where the recent discoveries are showing the connections between the earliest British settlements in America. For example, Bermuda limestone was found inside the Jamestowne fort site in a 1610 context. This was ballast used in the new ships built by the Sea Venture survivors.

We began our visit attending an art auction at the World Heritage Center in the town of St. George. Located at the northeast tip of Bermuda, St. George is a UNESCO World Heritage site. There are many buildings with limestone walls and roofs dating from the 1700s. Like in Williamsburg, St. George’s early structures survive due to 20th Century preservation efforts and the fact that the capital was moved in 1815 to Hamilton. St. George residents supported Washington with gunpowder during the revolution, in exchange for food, and traded for cotton with the Confederate blockade runners during the Civil War. The art auction was held in the 1860 building that served as a warehouse for the goods traded with the blockade runners. Nearby is the old Globe Hotel, once the headquarters of the commercial agents for the Confederacy, and now housing a related museum. We enjoyed climbing aboard the full size replica of the ship Deliverance built by Sea Venture survivors near what is now the town square.

We paid homage to those Sea Venture survivors by visiting the monument at the site, just to the east of St. George, where they struggled ashore. It was a balmy day, and we wondered why anyone would trade such a place for the heat and humidity of Tidewater Virginia. Indeed, the leaders had to use strict discipline to force the erstwhile Jamestowne settlers to leave. Even so, two men ran off and hid. They survived and later became part of the initial settlement of Bermuda.

We paid homage to those Sea Venture survivors by visiting the monument at the site, just to the east of St. George, where they struggled ashore. It was a balmy day, and we wondered why anyone would trade such a place for the heat and humidity of Tidewater Virginia. Indeed, the leaders had to use strict discipline to force the erstwhile Jamestowne settlers to leave. Even so, two men ran off and hid. They survived and later became part of the initial settlement of Bermuda.

One day we visited John Cox at his family home “Orange Valley.” Mr. Cox traces his lineage through several major Bermuda families back to the 1700s. His ancestor Captain William Cox built the home in 1802 and planted a now huge India rubber tree in the garden. John Cox has served in the Bermuda Historical Society for many years and has written several books about Bermuda in the 18th & 19th Centuries, when maritime trade provided the country’s economy. He gave us an inscribed copy of his Life in Old Bermuda. On another evening along with others from Williamsburg, we dined with Lucy and Mike Murphy at their home overlooking Hamilton Harbor. Several other Bermudians joined us and we enjoyed a lively conversation about their hopes and plans for developing the island while preserving its heritage. Large cruise ships are not bringing tourists who spend time getting to know Bermuda and its people. In contrast, we were in conversation with people who shared stories of their island lives. One such person is Winny, who led us on a memorable ride through the back roads of Somerset, where she grew up swimming around the docks and playing in the caverns of old British Fort Scaur. On every street there was a pretty pastel painted house where one of her family lived.

We visited the Masterworks Museum, a cultural gem where art depicting Bermuda is being collected. Many of these works were taken off the island, but are now being returned. Tom Butterfield, the museum director, showed us his prizes in the vault room, including two Winslow Homers and a Georgia O’Keefe. Upstairs, we visited an exhibit recalling Samuel Clemens’ affection for the island; he visited on 7 occasions, spending nearly 200 days on Bermuda. Connie and I empathize with the sentiment behind his quip: “You can go to heaven if you want. I’d rather stay here in Bermuda.”

Notes

1. Mark Twain’s first visit to Bermuda was at the conclusion of the 1867 trip to the Mediterranean that gave him the material for The Innocents Abroad. Bermuda gets a couple of paragraphs in Chapter 60.

2. For the history of the connection among Jamestowne, the Sea Venture and Bermuda: The Shipwreck that Saved Jamestown; Lorri Glover and Daniel Blake Smith; Holt Paperbacks, 2009.

3. If you have an interest in the maritime history of the Americas, from the Caribbean to the Canadian Maritimes, with a focus on Bermudians, I highly recommend In the Eye of All Trade; Michael J. Jarvis: UNC Press, paperback, 2012.

Share:

Recent Stories

- July 03, 2020 :: Greg McKelvey

Summer 2020 Ink Zone (#176) - April 07, 2020 :: Marey Barthoff

Oh Dear AAPA'ers - June 30, 2019 :: Clarence Wolfshohl

June 2019 AAPA Miscellany - September 25, 2018 :: Clarence Wolfshohl

Boar Finds a Comfortable Home - September 05, 2018 :: Greg & Sally McKelvey

Fall 2018 Ink Zone (#156) - August 01, 2017 :: Clarence Wolfshohl

July 2017 AAPA Miscellany - July 15, 2016 :: Clarence Wolfshohl

June 2016 AAPA Miscellany - January 29, 2015 :: Dave Griffin

AAPA MIscellany Premiers - February 26, 2015 :: Clarence Wolfshohl

April 2015 AAPA Miscellany - June 22, 2015 :: Clarence Wolfshohl

June 2015 AAPA Miscellany - June 22, 2015 ::

About E-Journals - June 19, 2015 :: Clarence Wolfshohl

Ernestine's Beauty Parlor - February 11, 2015 :: Delores Zillmer Miller

PICKING STONES AND BUILDING BARNS - April 28, 2015 :: Clarence Wolfshohl

NEVSKY PROSPECT - February 26, 2015 :: David Griffin

MEASURE - February 11, 2015 :: Sandra Gurev

HOME - February 02, 2015 :: Clarence Wolfshohl

MY LIFE WITH TOM - January 27, 2015 :: Sandra Gurev

SHE’S TROUBLE WITH A CAPITAL T - November 25, 2014 :: David Griffin

OLD SHOES - October 15, 2014 :: Sandra Gurev

THE MADCAP ADVENTURES OF ELIEZER GUREVITCH - August 13, 2014 :: Delores Miller

HUCK AND PUCK - July 26, 2014 :: David Griffin

Golden - July 11, 2014 :: Peter Schaub

The Isle of Devils - July 02, 2016 ::

AAPA E-Journal Listings - June 27, 2014 :: David Griffin

ANTHROPOLOGY

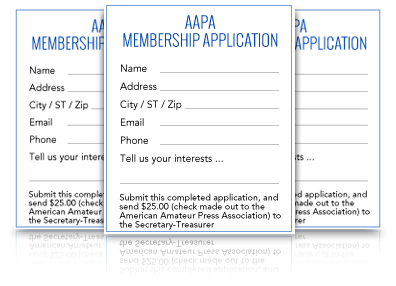

JOIN AAPA!

Become A Member!

Amateur journalism is a unique activity. Amateur journalists publish journals on paper & online & come from many perspectives: from deluxe letterpress printed journals, to Xeroxed newsletters, to artistically designed cards and ephemera. We embrace the spirit of being amateurs – loving what we do for pure joy and not financial gain – while creating top quality journals, zines, and homemade publications.

Amateur journalism is a unique activity. Amateur journalists publish journals on paper & online & come from many perspectives: from deluxe letterpress printed journals, to Xeroxed newsletters, to artistically designed cards and ephemera. We embrace the spirit of being amateurs – loving what we do for pure joy and not financial gain – while creating top quality journals, zines, and homemade publications.

Members receive ...

- The monthly bundle mailed via the postal service

- Access to the website and e-journals

- e-mailed updates

- Ability to publish your stories on AAPA

|

|