NEVSKY PROSPECT

There is nothing finer than Nevsky Avenue, not

in St. Petersburg at any rate; for in St. Petersburg

it is everything. –Nikolai Gogol

We enter onto Nevsky Prospect from the Moscow Station, from the east where the thoroughfare circles the obelisk monument in the middle of Ploshchad’ Vosstaniya (Vosstaniya Square). We have traveled all night by train from Moscow, leaving Moscow at 1:00 a.m. and arriving on this heavy, overcast August morning at 8:00. The sky settles around the railway cars as we step onto the open platform. The grey of the air grows dotted with darker grey shapes as the singing vacationers, who have made our journey like a holiday, descend from the train. But as the rhythm of the rails and the Russian ballads that lulled us to sleep several hours earlier vanishes as we stride toward the station, the raucous new rhythms of St. Petersburg begin.

Instead of the songs sung in unison (although not always harmoniously) by the celebrating vacationers the night before, several songs in competition assail us as we exit toward Ploshchad’ Vosstaniya. Three street musicians have positioned themselves along the passageway from the station’s doors to the sidewalk. Each sings a different song of a different genre. The closest leans against the blackened brown bricks, plays a balalaika, and croons what seems to be a ballad much like those we heard on the train. Further down the walkway, squatting on a wooden crate, another picks a guitar and sings John Lennon’s “Imagine.” And the third pipes on a flute a haunting melody from Asian Russia that is nearly stifled by the singers’ raised voices. He is nearly hidden in a still shadowed doorway, but his song manages to obtrude itself into the cacophony.

The gay carriages, the handsome men, the beautiful

women–all lend it a carnival air, an air that

you can almost inhale the moment you set foot on Nevsky Avenue.

–Gogol

On the sidewalk, the roar of truck and auto motors and the swish of tires and the honks, clanks, and grinds of all the automotive energy of a large city replace the three musicians. And except for the counterpoint of the sound of people–in normal city sidewalk conversation, in agitated loud complaint, or in angry confrontation–the sound of car, truck, bus, and trolley is the rhythm of this August day. Our destination is at the other end of the avenue, the Hermitage on the banks of the Neva River, and since we have over an hour before it opens, we decide to walk the three kilometers of Nevsky Prospect.

We finish the circle of Ploshchad’ Vosstaniya and look down the straight wide three kilometers lined with four and five story buildings in pastel greens and pinks and subtle earthen shades. The same thing strikes me here as in most of Moscow–the lack of signs, neon or plastic illuminated arches or globes or lobsters or other gigantic shapes designed to lure customers. A Baskin Robbins is marked with its pastel mauve and blue, and an Italian fast food place is highlighted with its bright red, white, and green sign inviting people in to its bright chrome and formica. But these are the exceptions. More typical is the large drug store whose front sprawls over half a dozen large display windows, all of which are empty except for one containing a solitary Tampex box.

Nowhere do people bow to each other with such

exquisite and natural grace as on Nevsky Avenue.

–Gogol

We finish the circle of Ploshchad’ Vosstaniya and walk into the middle of a street-fight. Here at 9:00 in the morning, two street people, swaying and incoherent, struggle in the center of their comrades, who form an inner ring, and curious pedestrians, who form an outer circle. As the two, a drunk young man and an equally inebriated young woman, stumble around each other, lurching forward or backward, the two rings expand or contract, open or close, like amoeba reacting to a stimulus. The brawling man could be handsome if cleaned up; he has a Scandinavian look, perhaps a descendent of the Varagins or Vikings who helped shape this far northern reach of Russia. His opponent, perhaps only hours ago his lover, has dirty-blond hair covering her face. Finally, she is unable to stand, but she lifts her body dazed from the man’s blows and the booze, stretches her arms out to comrades in the inner circle, and mumbles something to several of them. They hand her a bottle of vodka.

We edge our way out of the crowd and begin our walk down Nevsky. This prospect or avenue is probably the most famous street in Russia. Gogol makes it the main character in a short story and a contributing feature in most of his tales set in St. Petersburg. The Bolsheviks marched the same way we are walking when they attacked the Hermitage in the October Revolution. In Ten Days That Shook the World, John Reed describes the Revolutionaries wheeling around Ploshchad’ Vosstaniya on their way from Smolney, the one-time girls’ school that was the Bolshevik headquarters. In some of the faces we pass are eyes from an Eisenstein film.

At this time you can please yourself about your

dress. You can wear a workman’s cap instead of a hat,

and even if your collar were to stick out of your

cravat no one would notice it. –Gogol

The school-bus yellow trolleys, tethered to their electric lines, are jammed with riders. Each time a trolley stops, it consumes more passengers than it disgorges. We decide to ride one for a short distance just to say that we have done so. On the trolley are replicas of the people still walking beside us: old men with medals pinned to their chests, women in babushkas and with grocery bags, young men and women in blue jeans and t-shirts with English logos or announcements. The young man standing in front of me wears a mustard yellow t-shirt with “Lopez Island” printed over his heart. I wonder where Lopez Island is and where he got the shirt. When he twists around, I see the fake leather name patch on his jean pocket; it reads “Buck Rojers” with a j in “Rogers.” Someone in the front of the trolley has a boom-box– or perhaps the trolley has a radio–playing the Beatles.

We get off the trolley at Anichkovskiiy Most (or bridge) over the Fontanka River. The t-shirt of the young man on the trolley has put me in a wondering mode, and I wonder if this is the bridge from which the barber Ivan threw the nose he found in his onion roll in Gogol’s The Nose. There are many bridges in St. Petersburg, several along Nevsky Prospect. This first and biggest over the Fontanka, the next over the Griboyedov Canal, and the third over the Moyka River. Anichkovskiiy is probably the finest, at least on the avenue. My guidebook notes that Anichkovskiiy was built in 1839-41, with its crowning feature, the four statues of rearing horses and trainers, one at each corner of the structure, added later in the 1840’s. This would be a good bridge for Ivan to toss the nose into the river below, but it isn’t. Gogol wrote “The Nose” in the mid 30’s.

As we progress from Anichkovskiiy Most to the Narodnyy Most over the Moyka, we linger over the sights on Nevsky and make a few detours onto the by-streets. We pass by Anichkov Palace (the Palace of Pioneers) amidst one of St. Petersburg’s fine gardens, the statue of Catherine II, the public library, Gostinyy Dvor’s complex of department store and theaters.

All he wanted was to see the house of that

ravishing creature who seemed to have flown down

on Nevsky Avenue straight from heaven and who would

most probably fly away no one could tell where.

–Gogol

We follow Griboyedov Canal south for a few blocks to the entrance to a dark, non-descript building. A plaque at the door bears one of the few words in Cyrillic characters that I can recognize– (Lenin). I do not know what Lenin did at this spot–visited, plotted, slept; but on this overcast day, I can easily imagine Bolshevik strategy being shaped in the second-story room overlooking Griboyedov Canal. We retrace our steps north, back toward Nevsky and then across it, and see Resurrection rising from the banks of the canal to dominate the skyline with its one brilliant gold dome and, above all perched atop the tall tent-roof, the swirled blue and white turbined head. This is the Church of the Resurrection of Christ. It seems more distanced than a few blocks from the dark-faced building with Lenin stamped on a plaque. As Resurrection rises nearly 250 feet above the canal, it gathers our sight and perhaps our spirits into the swirls of that uppermost dome so that we spiral above the brick and pavement of Nevsky and all of St. Petersburg. But the grandeur of this Church of the Resurrection and any plotting done by Lenin a few blocks south across the Nevsky come from the same source. The church was built on the spot of the assassination of Alexander II in 1881. Returning to the Winter Palace after inspecting troops, Alexander was bombed by a member of the People’s Will organization, a step in the movement toward revolution.

He ran after the carriage which, luckily, did

not go far, stopping before the Kazan Cathedral.

He hastened into the cathedral, pushing his way

through the crowd of beggarwomen with bandaged faces

and only two slits for the eyes. –Gogol

We are silent as we walk back to Nevsky. But once we are back on that thoroughfare, the aspiration of the Church of the Resurrection gives way to the mammoth presence of Kazan Cathedral just west of the canal. If Resurrection makes us lift our thoughts to heaven, a heaven that may become translucent and hazy as the twist of blue and white on the highest dome dissolves in the lowering sky, Kazan sets us down firmly on earth. Its great concave portico of ninety-six Corinthian columns four rows deep pulls us into the interior of the arc. We wind around the marble columns as if in a labyrinth, the shadows deepening as we penetrate to the fourth row and the bas-relief exterior wall of the cathedral within. The biblical scenes on the relief are interspersed with statues of John the Baptist, Sts. Vladimir and Andrew, and Alexander Nevskiiy. And as we approach the darkest recess, the shadows so heavy that the bas-relief erases itself into a smudge, we hear the moans and then nearly stumble over the legs of a couple in the throes of their own saintly passion. We quickly retreat, both for their and our own privacy, and step back to take in the total front of Kazan, which since 1932 has been the Museum of the History of Religion and Atheism.

But strangest of all are the incidents that take

place on Nevsky Avenue. Oh, do not trust that Nevsky

Avenue. –Gogol

At the Moyka, we take another circuitous route. Using the dome of St. Isaac’s Cathedral as a landmark, we turn south off Nevsky Prospect onto Gogolya (Street). The street is named for Gogol, who lived near the intersection of it and Nevsky from 1833 to 1836. Here he began Dead Souls. St. Isaac’s lures us on. As we exit the narrow Gogolya into the wide Mayorova, another major prospect, we hear Dixieland–“When the Saints Go Marching In” followed by “Yankee Doodle”–coming from the steps of St. Isaac’s. A five-piece combo plays on the lower steps in front of the backdrop of World War II-scarred columns. Sightseers returning to the In-tourist bus down the block stroll by and drop money into the instrument cases. We circle the cathedral, the Bronze Horseman, the huge statue of Peter the Great bestride a serpent-stomping mount in Dekabristov Square, off to our left. As we round the third corner of St. Isaac’s, another In-tourist bus pulls to a stop along the curb in front of us. Two small children, one probably six or seven years old and the other just a toddler, curiously position themselves near the rear bus door. The door opens, and the older child slaps his brother, who falls to the sidewalk as if struck by the door. The toddler’s howl drowns out the Dixieland sounds that still float around the cathedral. His anguish-flushed face turned toward the exiting tourists and a now soothing arm around his accomplice, the older boy pleads with those exiting the bus. After a small crowd of passengers and a couple of pedestrians has gathered around the fallen and kneeling boys, a woman comes running from the steps of the cathedral. She had not been noticed before, but now she manifests worried and outraged motherhood. She is short, not much taller than the older boy, and evidently swarthy under the grime on her dress and face. She looks desperate sympathy toward her two children and incrimination toward the gathered crowd, who shift uneasily in their clean garments and fair skins under her darkling glare. The bus driver talks with the woman; soon they are both shouting but with a hint of bargaining in their tones. He shakes his head and speaks with some of his group as if he has been in this situation before, knowing they are being duped, but willing to surrender to the mother’s demands to escape her and her two sons’ curses and cries. Several of the men from the bus reach into their pockets and pass some bills to the driver, who counts them into the woman’s hand. The German tourists then follow the driver-guide up the steps of St. Isaac’s, and the gypsy band slips around to another side of this tourist attraction.

The sun burns off a bit of the overcast; blue patches open above Nevsky Prospect as we pass the Admiralty at the avenue’s end and stroll into Dvortsovaya Square with its towering Alexander Column in the center. Ringing the column on three sides are the various palaces of the Czars, but immediately before our eyes as we leave Nevsky Prospect behind this morning is the Winter Palace, the Hermitage. We skirt several workmen barricades and some excavation tools in the middle of the plaza. People are crisscrossing the square, but most seem headed in our direction, toward the entrance to the Hermitage museum. We pass the last construction barricade, and a man leading a bear passes us on his way to Nevsky Prospect.

Share:

Recent Stories

- July 03, 2020 :: Greg McKelvey

Summer 2020 Ink Zone (#176) - April 07, 2020 :: Marey Barthoff

Oh Dear AAPA'ers - June 30, 2019 :: Clarence Wolfshohl

June 2019 AAPA Miscellany - September 25, 2018 :: Clarence Wolfshohl

Boar Finds a Comfortable Home - September 05, 2018 :: Greg & Sally McKelvey

Fall 2018 Ink Zone (#156) - August 01, 2017 :: Clarence Wolfshohl

July 2017 AAPA Miscellany - July 15, 2016 :: Clarence Wolfshohl

June 2016 AAPA Miscellany - January 29, 2015 :: Dave Griffin

AAPA MIscellany Premiers - February 26, 2015 :: Clarence Wolfshohl

April 2015 AAPA Miscellany - June 22, 2015 :: Clarence Wolfshohl

June 2015 AAPA Miscellany - June 22, 2015 ::

About E-Journals - June 19, 2015 :: Clarence Wolfshohl

Ernestine's Beauty Parlor - February 11, 2015 :: Delores Zillmer Miller

PICKING STONES AND BUILDING BARNS - April 28, 2015 :: Clarence Wolfshohl

NEVSKY PROSPECT - February 26, 2015 :: David Griffin

MEASURE - February 11, 2015 :: Sandra Gurev

HOME - February 02, 2015 :: Clarence Wolfshohl

MY LIFE WITH TOM - January 27, 2015 :: Sandra Gurev

SHE’S TROUBLE WITH A CAPITAL T - November 25, 2014 :: David Griffin

OLD SHOES - October 15, 2014 :: Sandra Gurev

THE MADCAP ADVENTURES OF ELIEZER GUREVITCH - August 13, 2014 :: Delores Miller

HUCK AND PUCK - July 26, 2014 :: David Griffin

Golden - July 11, 2014 :: Peter Schaub

The Isle of Devils - July 02, 2016 ::

AAPA E-Journal Listings - June 27, 2014 :: David Griffin

ANTHROPOLOGY

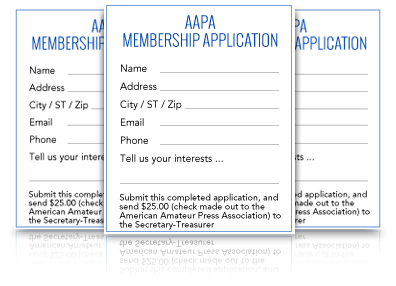

JOIN AAPA!

Become A Member!

Amateur journalism is a unique activity. Amateur journalists publish journals on paper & online & come from many perspectives: from deluxe letterpress printed journals, to Xeroxed newsletters, to artistically designed cards and ephemera. We embrace the spirit of being amateurs – loving what we do for pure joy and not financial gain – while creating top quality journals, zines, and homemade publications.

Amateur journalism is a unique activity. Amateur journalists publish journals on paper & online & come from many perspectives: from deluxe letterpress printed journals, to Xeroxed newsletters, to artistically designed cards and ephemera. We embrace the spirit of being amateurs – loving what we do for pure joy and not financial gain – while creating top quality journals, zines, and homemade publications.

Members receive ...

- The monthly bundle mailed via the postal service

- Access to the website and e-journals

- e-mailed updates

- Ability to publish your stories on AAPA

|

|