PICKING STONES AND BUILDING BARNS

One hundred and thirty five years ago our ancestors came from overseas to seek their fortune. Settled in Central Wisconsin, which was a wild land of forests, trees and rocks. In their German/Prussian/Poland homeland, they were peasants working for rich absentee landlords. Houses and barns were built together, the cow herds provided the heat for the house. Emigrant tickets were provided by relatives already in America. Here they decided to become dairy farmers.

Four feet of frost every winter forced boulders to the ground surface, which had to be picked before the land could be cultivated. A contraption known as a stone boat, 4 feet wide, twelve feet long, looped upwards in front and pulled by a good team of horses. These peasant children walked over the acres hoisting pebbles, rocks, stones, cobblestones and boulders. Sometimes the horses spooked and ran away, scattering stones over freshly picked soil.

In the early years of the twentieth century, farmers decided to build barns. The barn was essential for storage and livestock shelter. The good Lord had provided these rocks: granite, basalt, quartzite, sandstone. Masons worked for a dollar a day, building a stone wall, ten foot high, two feet deep, three feet in the ground. Rocks weighed about thirty pounds, and for a 36×50 foot barn, 4000 rocks were needed for the 272 feet total of rocks. Filled with a sand concrete mortar, huge boulders made the corner stones, chiseled the year. This took about six weeks, crews slept in tents, housewives cooked and baked each day to feed the crew. No one builds barns like this anymore, only in our memories the lore and legends remain.

Because the Good Lord again provided forests, trees to be hacked down, cut into lumber for the upper part of the barn. Tamarack, elm, oak, pine, hemlock. Lumber had to be air dried for a year before building or the green wood warped, twisted and bent. Another crew of carpenters, specialty barn builders came to frame the barn. Mortice and tenon frame. Floor joists, boards, beams, rigid rafters, oak wood pegged. All hand tools, no electricity, no hydraulic lifts. Axes, froes, saws, adzs, bull work by strong men. Oak pegs, square nails. Gable type roof, covered with red cedar shingles, which again the Good Lord provided in the swamps.

More rocks and boulders were gathered by the children, with the team of horses and stone boat to build a ramp leading to the upper part of the barn, so wagon loads of feed could be hauled right in the barn. Bundles of oats, wheat and timothy hay. Chutes and ladders reached to the stone basement so one did not have to fight the elements in winter. Home for the doves and barn swallows.

Probably a barn dance was held after to celebrate the new barn, and repay all the workers with kegs of beer, hard liquor, good food.

Michael Zillmer (1814-1895) migrated to Dupont in 1879. His son John Albert Zillmer who married Fredricka Lembke in 1888 probably built the first barn on the acreage, after clearing the hardwood trees. John Albert’s son William, born in 1896 took over the farm after his Father’s death in 1936. In turn William’s son Wilbert born in 1930 began management in 1953, which eventually passed to his son Bruce, who today in 2015 dairy farms.

After World War One and the great depression, World War Two was raging in Europe and demand for dairy and beef and pork and chicken products increased. Prices were good, so it was decided to again enlarge the barn in 1944. Even though rationing forbid purchasing supplies, the Zillmer swamp provided the lumber, down to the cedar shingles. Again rocks and stones were picked from the fields, even borrowing, begging or buying boulders from the neighbors. About the only thing purchased was a keg of nails.

In the spring of 1944 construction began on the barn extension. Neighbors were asked to help and they did. Neighboring women came to make food for the hungry workers.

Because of state dairy inspectors, the milking equipment could no longer be stored outside on a wooden platform. Blue cinder blocks were used by the masons to construct a milk house, for the many milk cans, DeLaval milkers. Water piped in a cement tank to cool the milk, with the overflow water piped outside for thirsty cows. Eight to ten milk cans were picked up by the Quarterline Cheese Factory and the driver Mike Polzin. Extra cinder blocks were used to build a smoke house.

Barns in Wisconsin are disappearing at an alarming rate. Upkeep is expensive, a new roof is exorbitant.. Frost heaves the stone walls, causing them to crumble.

I flip through pictures

Some are so great

So many memories

Some should be thrown away

But not the ones of me

And the building on to the barn

Erect now and secure

Weathered and worn –

Faithfully it still stands.

No one picks stones nor builds dairy barns any more. The barn stood for both community and family unity, cemented by honest sweat. The farmers took pride in keeping a neat barn. The barns were an icon, an image that stands for something.

copyright 2015 Delores and Russell Miller

Delores Miller lives with husband Russell in Hortonville, Wisconsin. In the summer of 2007 they celebrated their 50th wedding anniversary with a party hosted by their five children and ten grandchildren. It’s been a long road. Dairy farming until retirement in 1993, they continued to ‘work’ the land, making a subdivision of 39 new homes on their former hay fields.

Share:

Recent Stories

- July 03, 2020 :: Greg McKelvey

Summer 2020 Ink Zone (#176) - April 07, 2020 :: Marey Barthoff

Oh Dear AAPA'ers - June 30, 2019 :: Clarence Wolfshohl

June 2019 AAPA Miscellany - September 25, 2018 :: Clarence Wolfshohl

Boar Finds a Comfortable Home - September 05, 2018 :: Greg & Sally McKelvey

Fall 2018 Ink Zone (#156) - August 01, 2017 :: Clarence Wolfshohl

July 2017 AAPA Miscellany - July 15, 2016 :: Clarence Wolfshohl

June 2016 AAPA Miscellany - January 29, 2015 :: Dave Griffin

AAPA MIscellany Premiers - February 26, 2015 :: Clarence Wolfshohl

April 2015 AAPA Miscellany - June 22, 2015 :: Clarence Wolfshohl

June 2015 AAPA Miscellany - June 22, 2015 ::

About E-Journals - June 19, 2015 :: Clarence Wolfshohl

Ernestine's Beauty Parlor - February 11, 2015 :: Delores Zillmer Miller

PICKING STONES AND BUILDING BARNS - April 28, 2015 :: Clarence Wolfshohl

NEVSKY PROSPECT - February 26, 2015 :: David Griffin

MEASURE - February 11, 2015 :: Sandra Gurev

HOME - February 02, 2015 :: Clarence Wolfshohl

MY LIFE WITH TOM - January 27, 2015 :: Sandra Gurev

SHE’S TROUBLE WITH A CAPITAL T - November 25, 2014 :: David Griffin

OLD SHOES - October 15, 2014 :: Sandra Gurev

THE MADCAP ADVENTURES OF ELIEZER GUREVITCH - August 13, 2014 :: Delores Miller

HUCK AND PUCK - July 26, 2014 :: David Griffin

Golden - July 11, 2014 :: Peter Schaub

The Isle of Devils - July 02, 2016 ::

AAPA E-Journal Listings - June 27, 2014 :: David Griffin

ANTHROPOLOGY

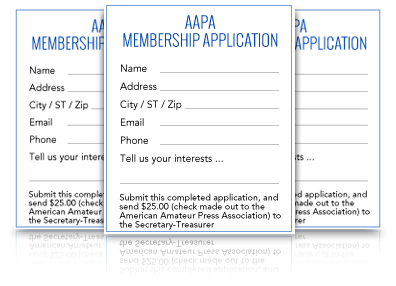

JOIN AAPA!

Become A Member!

Amateur journalism is a unique activity. Amateur journalists publish journals on paper & online & come from many perspectives: from deluxe letterpress printed journals, to Xeroxed newsletters, to artistically designed cards and ephemera. We embrace the spirit of being amateurs – loving what we do for pure joy and not financial gain – while creating top quality journals, zines, and homemade publications.

Amateur journalism is a unique activity. Amateur journalists publish journals on paper & online & come from many perspectives: from deluxe letterpress printed journals, to Xeroxed newsletters, to artistically designed cards and ephemera. We embrace the spirit of being amateurs – loving what we do for pure joy and not financial gain – while creating top quality journals, zines, and homemade publications.

Members receive ...

- The monthly bundle mailed via the postal service

- Access to the website and e-journals

- e-mailed updates

- Ability to publish your stories on AAPA

|

|