MY LIFE WITH TOM

Those of us in the business of the word gather magnificent companions. That is, we make friends with those with whom we are constantly in communication or communion–the writers we read. For we tend to do more than read their works–listen to their side of the conversation. We observe them, go behind their backs to converse with others about them, travel around to see where they have been. It makes no matter if our friends are alive or dead–I dare say, most are legally dead. But to us they are alive and very much parts of our lives.

I have a friend–alive, tangible, still making his physical way on earth–who became enamored of Jane Austen. I do not know what it is about her, but he went so far as to become a member of the Jane Austen society. To me he seems well acquainted with her, having read her novels multiple times and knowing something about her environment. If she were a contemporary movie star, we might see him on the news arrested for stalking her. But she is dead, so he is free to go through whatever of her refuse he can find. Not long ago, he went to the society’s annual national convention and came back humbled: how little he knew about Jane. Compared to her other friends at the affair, he was a mere acquaintance. Those others really knew her. The color of her eyes; one cannot learn that from that one silhouette representation of her in Winchester Cathedral, but the close friends of Jane knew the color.

As I said, we in the business of the word often come to know one or two or a group of writers as if they were neighbors, friends, or even family members. Take my friendship with Tom, or as you may know him, Thomas Carlyle. Now, let’s not start out with that attitude or name-calling. I know he has had his share of detractors, but he has been quoted out of context too much. And I know the context itself is sometimes to blame. I sometimes wish he had not read all those Germans–although, I must confess, his use of the word Teufelsdröck was one of the things that first impressed me, besides his Ancient Mariner glittering cold gray Scottish eyes. (See, I know the color of his eyes). But Tom is the kind of friend–of flesh and blood or of the intellect–we all probably have. We excuse their faults because they are our friends. We find something about them that compensates for those faults. I don’t know what it is about Tom that lets me accept his bombastic coruscations or his archly conservative and politically incorrect ideas. (Well, again, I have to confess, the latter may be like his use of vulgar German). I would like to tell you how I came to know old Tom and became such close pals that I visited his home.

I can not remember if I ever met Thomas Carlyle before I completed my bachelors. Perhaps, I caught a glimpse of him in high school–a paragraph of Past and Present from “The Midas Touch,” that horrific-sentimental anecdote about the Irish woman killing her children for the insurance money to fed the rest of her family. I can not remember, and we have shared that story so often now that I can not remember when I first heard it. But I can remember when his pronouncement of Teufelsdröck first swam into my ken. I had finished my BA at mid-semester. I didn’t know what I wanted to do with my life. Teaching was a vague possibility, but I did not even look for a teaching job. I returned to my home in San Antonio, after a few beers agreed to go to work for a carpenter friend of mine, and saw an ad in the newspaper about courses being offered in the spring semester at Trinity University. I decided to register for a few classes in their master’s program. The three courses were literary criticism and post-Civil War American literature on Tuesday and Thursday mornings and Victorian prose on Wednesday evenings.

I remember little of the morning classes, except the only friend in the batch was Mark Twain, but I can tell you nearly everything about the Victorian prose class, down to the color of the professor’s socks. He was a tall, gaunt fellow with an intellectual paunch who lectured with one leg drawn up on the desk, his arms wrapped around the folded knee and the text of study. At times, as if to punctuate his transition from expounding on the work to reading from the text, he would scratch vigorously at the bare leg between his down gyved sock and his pants leg pulled up nearly to his knee by the stretching action of his pose. They were generally gray–his socks, that is. He was the one who introduced me to Tom.

Through the forty plus years I taught, the lengths and number of my assignments dwindled. Most of my colleagues tell me they have had the same experience. The course in Victorian prose was sufficiently Victorian in volume. We interspersed novels with major excerpts from the essayists throughout the semester: Dickens’s Bleak House, Eliot’s Middlemarch, Thackeray’s Vanity Fair, Meredith’s The Ordeal of Richard Feveral, Gissing’s New Grub Street, Moore’s Esther Waters, every other week, interspersed with Macaulay, Newman, . . . well, you know them–from the Apologia pro Vita Sua to Ruskin’s Venetian stones. There was so much, that someone could have easily been smothered in all the crinoline and antimadagascars. But early in the semester I fell into a routine with a friend–flesh and blood–from my neighborhood. I met him at a local bar and grill after class each Wednesday and relived the experience of the class. Perhaps this is when I fully decided to become a teacher. He had completed only a year of junior college before he went to work at the family florist shop, but he eagerly heard my explanations of the novels or ideas of the essays. We generally parted at closing time–midnight–and, even though we often hung out together, especially fishing, on the weekends, we did not discuss the literature except on Wednesday nights. Until my professor of the down-gyved sock assigned Tom. We had excerpts from Past and Present and Heroes, and the central three chapters of Sartor Resartus. Those three chapters! I have not been the same since. But the real kicker is that Darrell, my Wednesday night bar and grill class of one, wanted to carry on after midnight out on the curb in front of the bar and while trying to lure a notorious five pound bass down on the Guadalupe that weekend. Well, perhaps, it was more my desire to carry on about Tom.

What captivated Darrell and me was the Centre of Indifference, our being in our own such center. As we began the second round of beer, I read the last sentence of Teufelsdröck’s wrestling with the Devil on the Rue Saint-Thomas de l’Enfer in “The Everlasting No.” After Carlyle’s German professor defies Universal Darkness with “I am not thine, but Free,” he says, “It is from this hour that I incline to date my Spiritual New-birth, or Baphometic Fire-baptism; perhaps I directly thereupon began to be a Man.” (With a capital M). That declaration of independence from all the dross of the world rushed over us a fire-baptism. Remember, this was happening only a few months after the assassination of John F. Kennedy and before Tonkin Gulf. News reportage from Vietnam was slowly shouldering its way onto the front page. A month after that heady night, we drank a farewell beer with a friend from high school who was shipping out as a Green Beret. He never came back.

So, when Carlyle took us in the next few pages into the Centre of Indifference and onto the Marchfield and Wagram battlefields, where thirty young men from a British Dumdrudge and an equal thirty from a French Dumdrudge meet to “blow the souls out of one another,” we knew if Tom had been a twentieth-century Texan from the eastside of San Antonio, he would have joined us for a beer.

I had still not seen Carlyle, met him face to face, so to speak. It had been more like an interview over the telephone. I heard his Scotch burr and caught clearly enough the laughter and angst in his vision, but I wondered about the physical presence of the man. And then a short while later, I saw him quite by accident. In the library searching for a topic for a research paper in the Victorian prose class, I drew from the shelves several general studies to get an overview of the period. In one–Jerome Buckley’s classic, The Victorian Temper–was reprinted the 1832 sketch of Carlyle by Daniel Maclise. Made shortly after the Carlyles moved to London from the remote Craiggenputtock, the Scottish farm to which he retreated with his new wife, Jane, to write Sartor Resartus, the sketch portrays Tom full length, leaning against a massive column with what Jane called his dandy hat in his hand. He struck me as a possible fifth Beatle, that new rock group that had been introduced to the United States about a month previously. I finally could put a face with the name and the voice.

The semester rolled on through Bleak House, Middlemarch, Mill’s On Liberty, and Ruskin’s Seven Lamps of Architecture. I had little time to spend with Tom. But as the end of April loomed and I received a graduate assistantship at the University of Idaho for the fall, I was given a present by a young woman I had spent some time with during this spring. She had found an old copy of Sartor Resartus, one of the Atheneum series from the late 1800’s, which were pocketbook-sized and featured pretty covers and frontispiece illustrations of the authors. There he stared out from the page, his head leaning on his hand with his fingers folded into a healthy shock of hair. He was older than the thirty-seven years of Maclise’s sketch, but smile lines creased his face. I was elated by the gift, and I tried to remember if I had wasted one of the young woman’s evenings with my talk about Carlyle. No, she said, but she could tell by my intensity that somehow Thomas Carlyle was important to me and she had just happened to see this volume at a used book sale. That young woman became my wife.

Thinking now of those artist renditions of Carlyle conjures the photographic images of old Tom that I’ve seen through the years since 1964. In an 1854 photo, he resembles a snuff-dipping Jimmy Stewart, the pocket under his lower lip protruding as if he had rested his tongue there. An 1855 photo is reminiscent of the famous Rossetti sketch of Tennyson reading Maud. Carlyle loved to ride, and took his horse out nearly daily; in an 1874 picture he appears with a riding crop or cane and his wide-brimmed hat, looking like a Scottish cowboy companion of Jesse Chisholm. All of these present Carlyle alone: I can recall only one of him with Jane. Actually Tom is with three women in the photograph. Jane and Lady Louisa Ashburton are to Tom’s left, Jane and Tom almost insubstantially sandwiching the British firmness of Lady Ashburton. A third, unidentified woman sits in the background. They are all on the granite steps of some Corinthian-columned building. Thomas is slightly but noticeably removed from the grouping of women. His hands are clasped in his lap as if in earnest Scotch prayer with his eyes shooting upward and toward his right in supplication to be elsewhere. I imagine it was a shopping trip. Years later, that is recently, I ran across a photo of an older him with Ralph Waldo Emerson’s grandson on his knee. Neither looks particularly happy. But then none of Carlyle’s photographs capture his smile. His illustrators do capture it. Perhaps that is the typical nineteenth-century relation to the camera, for not many of the Victorians–earnest or not–smiled for the camera. But Tom–the stormy sophist with his mouth of thunder, as Swinburne described him–has a smile, often like a cat’s eating a mouse.

The next fall I began graduate school. My acquaintance–nay, friendship–with Tom would grow greatly in the next few years as I wound my way through the intricacies of master thesis and doctoral dissertation. However, I did not set out to cultivate it. As much as I had been charmed by all the Victorians in that class with the professor of the down-gyved socks, I thought of twentieth-century authors when I looked into my future. I had become well acquainted with Aldous Huxley since I first encountered his Brave New World along with J. D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye and Jack Kerouac’s On the Road in high school. These, of course, were the cult classics of my generation, but Huxley had particularly appealed to me after I read his cautionary sequel to Brave New World, Brave New World Revisited. By the time I had my bachelors, I had read most of the novels and a good portion of the essays. When I began thinking about master’s thesis, Huxley was my only thought until I met with my graduate advisor to discuss finding a thesis director. No one on the faculty wished to direct a thesis on Huxley. In fact, the only person interested in post WWI literature at the University of Idaho was the folklorist who was blazing a new trail into urban legends and not interested in the more traditional literary fare.

The next fall I began graduate school. My acquaintance–nay, friendship–with Tom would grow greatly in the next few years as I wound my way through the intricacies of master thesis and doctoral dissertation. However, I did not set out to cultivate it. As much as I had been charmed by all the Victorians in that class with the professor of the down-gyved socks, I thought of twentieth-century authors when I looked into my future. I had become well acquainted with Aldous Huxley since I first encountered his Brave New World along with J. D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye and Jack Kerouac’s On the Road in high school. These, of course, were the cult classics of my generation, but Huxley had particularly appealed to me after I read his cautionary sequel to Brave New World, Brave New World Revisited. By the time I had my bachelors, I had read most of the novels and a good portion of the essays. When I began thinking about master’s thesis, Huxley was my only thought until I met with my graduate advisor to discuss finding a thesis director. No one on the faculty wished to direct a thesis on Huxley. In fact, the only person interested in post WWI literature at the University of Idaho was the folklorist who was blazing a new trail into urban legends and not interested in the more traditional literary fare.

By the time I had to form a thesis committee during my second year, I had proposed and rejected nearly every Victorian I knew, but Carlyle was always edging into my internal discussions. I would just sit down with Dickens to enjoy a porkpie or listen to Edgar Johnson tell me how Dickens researched Hard Times when up would pop Tom as the dedicatee of the novel. Or I would stroll along with Robert Browning, discussing Sordello, and around the corner would come Carlyle asking to borrow Browning’s copy of a 1662 book on the Fens in Cambridgeshire to research his book on Cromwell. So I set aside Johnson’s Dickens and Browning’s monologues and started the trek through the six volumes of David Alec Wilson’s life of Carlyle. We had arrived on London’s Cheyne Row to spend the rest of Tom’s life when the deadline to announce my thesis intentions arrived. I knew Carlyle had been invading my time with the other Victorians for a reason, but what should I write about him that had not already been written?

My thesis director, Professor Floyd Tolleson, was a forward-looking scholar. He skillfully maneuvered one of our discussions in the direction of stylistics, and we pondered the debate about the source of Carlyle’s rapsodico-reflective style. Was it really a result of his early work introducing German thought to England or was it the echo of his early exposure to the sermons of the Burgher Scotch Seceders ministers in Ecclefechan, his hometown? How could one really decide? Somewhere in Professor’s Tolleson’s psyche lurked a scientist, for he insisted the only way to really decide was through quantitative analysis. The University had recently purchased a computer system–a machine as large as several delivery vans, which used punch cards, the kind that had inspired the old jokes about folding, spindling, and mutilating. With a Carlylean glint in his eye, Professor Tolleson proposed we utilize this technology, for it was the wave of the future. I had my doubts–all those warnings from Huxley. But I did see the merit of his proposal to do a quantitative analysis of Tom’s language.

However, the servants of the computer did not share my acquiescence or my Professor’s enthusiastic vision. They were highly protective of their monstrous god, deigning to use it only for rituals of the most sacred university order, such as registration and comptrolling. Mere laypersons of the academic sect were incapable of using its exalted services. We could not use the computer. But I did end up doing the analysis, albeit of a more limited sampling of Carlyle’s writing because I had to use the built-in computer we all have, plus my fingers and toes.

Thus began my scholarly life with Tom. The springtime idyll in San Antonio became a fond memory of youthful comraderie, for henceforward we would be locked in serious dialogue that would determine my future. It lead to my masters and, then fully committed, to my doctorate. But I did not continue the friendship as strongly after finishing graduate school. At least, as strongly as I had envisioned often in those years of closeness. I foresaw years of teaching the Victorians, each time starting with Sartor Resartus, to which nearly all the rest of the century is a reaction. I would define that book at last. I would rescue Tom from the bad press of the mid-twentieth century. What else are friends for? I would make those smug Arnoldians eat their jeers of “moral desperado” that Matthew hurled at Thomas. They would come to appreciate the fact that moral desperadoism was perhaps the only legitimate calling in this post modern world.

However, to quote Tom’s fellow Scot, who a few times in his life sauntered down the high street of Ecclefechan, “The best laid schemes . . . gang aft agley.” Since graduate school, I have been able to teach the Victorians fewer times than Robert Burns visited Tom’s hometown. The one time I used Sartor to set the tone for the class, the students panicked at the first mention of Teufelsdröck, so I have not used that ploy again.

For twenty years I kept in touch, but you know how that goes. Visits become less frequent. New acquaintances become friends. Some old friends re-enter our lives. I taught Dickens fairly often; the students found him more congenial. I browsed recent scholarship on Tom, read Kaplan’s biography, read a few of Jane and Tom’s recently edited letters, but I never did pry too much into his married life. James Anthony Froude had done enough or too much of that. I felt it was not the one thing needful.

Then another fortuitous occurrence. A friend, an Arnoldian but not completely smug, sent me a photo of himself standing in front of the Carlyles’ house on Cheyne Row. It was a friendly gesture, but you never can tell about Arnoldians. Was the photograph secretly asserting, “How do you like this touchstone, you moral desperado? Get a little culture, why don’t you?” This same friend and I had debated the issue of the Hyde Park Riots in the guises of Matthew and Thomas respectively as guest lecturers in Paul Davis’s Victorian class at the University of New Mexico, so I wondered if the old debate was still fomenting. But the photo had a positive result because it made me determined to get my own picture taken on the steps to # 5 (now 24) Cheyne Row in Chelsea.

And that is how I went to visit my friend Tom at his home. Twenty years after the debate about the Hyde Park Riots, the young lady who gave me that first small volume with Carlyle’s picture and our daughter and I walked across half of London to visit Carlyle’s London home–a very Dickensian thing to do, but we did it because the underground was on strike and surface traffic was a snarled disaster. We sat out back in his small, high-fenced garden imagining smoking a pipe with Tom just as Tennyson used to do with him and Jane. We toured the rooms, the one at the top that Jane had built to get him above the noise so that he could write and the parlor where he and Jane are pictured in that hideous painting by Robert Tait. We walked down the street toward the Thames where a small park surrounds the statue of Carlyle by Jacob Boehm, erected in 1881, the year Tom died.

An identical statue looks down the High Street of his hometown. The next day we drove north just across the Scottish border to Ecclefechan. Ecclefechan is Tom’s birthplace, so we would visit the house in which he was born, the church in which his parents worshiped, the foundation remnants of the school where he first learned to read and write, and his grave. But first, we rented rooms at the Ecclefechan Hotel, the owner of which claimed that Burns had stayed there and that Carlyle’s father, who was a mason, had worked on it. At the exit to the village, we noticed a road sign indicating that Lockerbie, the site of the Pan-Am Flight 103 tragedy, was about ten miles up the road. But as we sat in the hotel lounge, sipping ale, none of the locals mentioned it. They were busy making jokes about a couple of salmon fishermen who just left and complaining about the new golf courses being constructed between Ecclefechan and Lockerbie by a Japanese firm. The day had been overcast and rainy, but shortly before sunset, the sky cleared in the west. We decided to stroll up High Street as the clouds rolled away. The statue was silhouetted against the sinking sun and began to glimmer when the sun’s dying rays caught the wet sheen of Carlyle’s arms and shoulders and head. My wife said, “The old man’s greeting you.” I said, “It’s good to see you, Tom.”

Clarence Wolfshohl is professor emeritus of English at William Woods University. He has published both creative and scholarly writing in small press and academic journals. He is a member of AAPA and operates El Grito del Lobo Press. A native Texan, Wolfshohl now lives with his writing, two dogs and one cat in a nine-acre woods outside of Fulton, Missouri.

Share:

Recent Stories

- February 27, 2026 :: Greg McKelvey

Moods - February 14, 2026 :: Greg McKelvey

Ink Free No. 22 (December 2024) - February 14, 2026 :: Greg McKelvey

Ink Free No. 21 (December 2024) - January 23, 2026 :: Greg McKelvey

Ink Free No. 20 (November 2024) - January 23, 2026 :: Greg McKelvey

Ink Free No. 19 (November 2024) - January 06, 2026 :: Greg McKelvey

Ink Free No. 18 (October 2024) - January 06, 2026 :: Greg McKelvey

Ink Free No. 17 (September 2024) - November 29, 2025 :: Greg McKelvey

Ink Free No. 16 (September 2024) - November 29, 2025 :: Greg McKelvey

Ink Free No. 15 (September 2024) - November 22, 2025 :: Greg McKelvey

Ink Free No. 14 (September 2024) - November 22, 2025 :: Greg McKelvey

Ink Free No. 13 (August 2024) - November 02, 2025 :: Greg McKelvey

Ink Free No. 12 (August 2024) - November 02, 2025 :: Greg McKelvey

Ink Free No. 11 (August 2024) - October 25, 2025 :: Greg McKelvey

Ink Free No. 10 (August 2024) - October 25, 2025 :: Greg McKelvey

Ink Free No. 9 (July 2024) - October 15, 2025 :: Greg McKelvey

Ink Free No. 8 (July 2024) - October 14, 2025 :: Greg McKelvey

Ink Free No. 7 (June 2024) - October 07, 2025 :: Greg McKelvey

Ink Free No. 6 (June 2024) - October 07, 2025 :: Greg McKelvey

Ink Free No. 5 (September 2024) - September 28, 2025 :: Greg McKelvey

Ink Free No. 4 (August 2024) - September 28, 2025 :: Greg McKelvey

Ink Free No. 3 (August 2024) - September 20, 2025 :: Greg McKelvey

Ink Free No. 2 (July 2024) - September 20, 2025 :: Greg McKelvey

Ink Free No. 1 (June 2024) - July 03, 2020 :: Greg McKelvey

Summer 2020 Ink Zone (#176) - April 07, 2020 :: Marey Barthoff

Oh Dear AAPA'ers - June 30, 2019 :: Clarence Wolfshohl

June 2019 AAPA Miscellany - September 25, 2018 :: Clarence Wolfshohl

Boar Finds a Comfortable Home - September 05, 2018 :: Greg & Sally McKelvey

Fall 2018 Ink Zone (#156) - August 01, 2017 :: Clarence Wolfshohl

July 2017 AAPA Miscellany - July 15, 2016 :: Clarence Wolfshohl

June 2016 AAPA Miscellany - January 29, 2015 :: Dave Griffin

AAPA MIscellany Premiers - February 26, 2015 :: Clarence Wolfshohl

April 2015 AAPA Miscellany - June 22, 2015 :: Clarence Wolfshohl

June 2015 AAPA Miscellany - June 22, 2015 ::

About E-Journals - June 19, 2015 :: Clarence Wolfshohl

Ernestine's Beauty Parlor - February 11, 2015 :: Delores Zillmer Miller

PICKING STONES AND BUILDING BARNS - April 28, 2015 :: Clarence Wolfshohl

NEVSKY PROSPECT - February 26, 2015 :: David Griffin

MEASURE - February 11, 2015 :: Sandra Gurev

HOME - February 02, 2015 :: Clarence Wolfshohl

MY LIFE WITH TOM - January 27, 2015 :: Sandra Gurev

SHE’S TROUBLE WITH A CAPITAL T - November 25, 2014 :: David Griffin

OLD SHOES - October 15, 2014 :: Sandra Gurev

THE MADCAP ADVENTURES OF ELIEZER GUREVITCH - August 13, 2014 :: Delores Miller

HUCK AND PUCK - July 26, 2014 :: David Griffin

Golden - July 11, 2014 :: Peter Schaub

The Isle of Devils - July 02, 2016 ::

AAPA E-Journal Listings - June 27, 2014 :: David Griffin

ANTHROPOLOGY

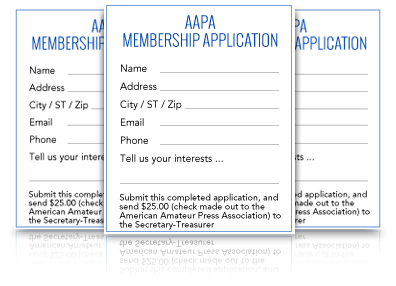

JOIN AAPA!

Become A Member!

Amateur journalism is a unique activity. Amateur journalists publish journals on paper & online & come from many perspectives: from deluxe letterpress printed journals, to Xeroxed newsletters, to artistically designed cards and ephemera. We embrace the spirit of being amateurs – loving what we do for pure joy and not financial gain – while creating top quality journals, zines, and homemade publications.

Amateur journalism is a unique activity. Amateur journalists publish journals on paper & online & come from many perspectives: from deluxe letterpress printed journals, to Xeroxed newsletters, to artistically designed cards and ephemera. We embrace the spirit of being amateurs – loving what we do for pure joy and not financial gain – while creating top quality journals, zines, and homemade publications.

Members receive ...

- The monthly bundle mailed via the postal service

- Access to the website and e-journals

- e-mailed updates

- Ability to publish your stories on AAPA

|

|